By: Zachary Draves

In the 1970’s, Black America was in the throes of a cultural revolution the likes of which not seen since the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920’s. It was a time where art, music, fashion, film, TV, and sports were front and center in elevating blackness to an unprecedented stature in American popular culture. All of which was rooted in the rallying cry of “black is beautiful” coming out of the civil rights and black power movements of the 1960’s.

A time where black cultural and political figures were asserting themselves in a way that would be characterized today as being “unapologetically black”. Everything from wearing afros and dashikis to more overt political activism were in pursuit of continuing the struggle for equality.

(Courtesy: Pirkle Jones)

In 1971, the Congressional Black Caucus was formed giving voice to black communities in Washington DC. In 1972, Rev. Jesse Jackson founded Operation PUSH and was preaching to young black people that they were somebody. That same year, Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm declared that she was “unbought and unbossed” in her historic presidential campaign. In March there was the National Black Political Convention in Gary, Indiana where black activists and politicians put forward an agenda that focused squarely on the interest of black people.

(Courtesy: Bettman Archive/Getty Images)

Musicians such as Marvin Gaye, Stevie Wonder, Curtis Mayfield, and Aretha Franklin were taking control over their creativity and putting out some of their best work that spoke to the black experience. Television programs such as Soul!, Soul Train, and Black Journal broke through an overwhelmingly white media landscape and put black culture and black concerns first. Authors such as Maya Angelou, Alice Walker, Toni Morrison, and Ntozake Shange wrote about the experiences of black women against the backdrop of a white dominated second wave feminism.

Athletes such as Curt Flood, Hank Aaron, and Arthur Ashe would challenge hierarchy in sports with their superb talent and willingness to speak truth to power on everything from baseball’s Reserve Clause to Apartheid in South Africa.

Simply put, it was a transformative decade of one cultural touchstone moment after another that would go on to have lasting effects.

But what happened in the NBA during this period was a combination of all of these sensibilities.

In the new book Black Ball: Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Spencer Haywood, and the Generation that Saved the Soul of the NBA, Dr. Theresa Runstedtler, a historian on race and sport at American University, provides a compelling insight into the lives and labor of black professional basketball players in the 1970s that would usher in a new era of player empowerment that was pivotal both on and off the court.

(Courtesy: AP Photo/George Brich)

The historically pervasive narrative surrounding the NBA and ABA, its razzle dazzle rival league during this era is that it was an overwhelmingly black league filled with individual renegades who were caught up in their own pomp and circumstance, that they were overpaid, where cocaine usage was rampant, and anything remotely associated with the concept of team was obsolete. Thus, there was a steep decline in television ratings, the NBA Finals were on tape delay, fans weren’t interested, and teams were losing money and sponsorships.

All of which was against the backdrop of white anxiety toward black social mobility and a heightened criminalization of black communities under the guise of “law and order”. The culmination of that sentiment was the official “War on Drugs” that started under President Richard Nixon, which led to the fifty year long ballooning of the prison population that is mostly comprised of black and brown people for non-violent drug offenses.

Much of these attidues stem in part from an infamous Washington Post article by Chris Cobbs that came out in 1980 where he claimed that 75% of NBA players used cocaine. For Dr. Rundstedler, these assumptions made against the players considering that just a decade prior the league was mostly white and held in high regard sparked curiosity about how race and the NBA specifically became the scapegoat.

“I was like what is that racial dynamic going on there, what does that mean?” she said. “That was my entry point into this broader story about race and labor in professional basketball in the 1970s. I wanted to figure out why was that narrative the way it was, was it true, was it a racialized way of talking about things that were going on beyond the basketball court in cities across the country?”

According to Dr. Rundstedler, that racial dimension was clear in the perplexed reaction on the part of white fans and media to the talent of these black players who played a style of ball that came from the urban streets of America that was perceived as showboating and undisciplined. She points out, on the one hand, they were amazed with the likes of Julius “Dr. J” Erving whose talent emerged out of those settings and on the other horrified and felt that they were ruining the purity of the game.

(Courtesy: Robert Washington)

“If they let things get too out of control, this would ruin the sport” she says. “The playing style from the previous decade was “team oriented”, it was about systemes, it was about running the plays, rather than individual feats and athleticism. So you see aspects of black ball players’ experiences from playground courts or summer leagues. I’m thinking of the Rucker and summer leagues in Philadelphia. You see that infiltrating professional basketball and the writers are like this might not be the greatest thing.”

Among the central figures in the book are Haywood, Kareem Abdul Jabbar, and Oscar Robertson. Each of them would challenge the standard operations of professional basketball in how it was played.

Haywood, who played in the NBA and ABA from 1969-1983, was the pioneering force behind players going straight from high school to the pros after he challenged the NBA on its eligibility rules. At the time, the NBA required that players had to complete four years of high school in order to be drafted. Haywood did just that when he was drafted by the Denver Rockets of the ABA in 1969 after his sophomore year at the University of Denver.

(Courtesy: AP Photo/Harold Filan)

He was granted an exception to the rule due to hardship given that he had come from a family of ten children in Mississippi and his mother was picking cotton for $2 a day.

In 1970, he signed a six year $1.5 million contract with the Seattle Supersonics before the NBA ruled that it violated the league rule and threatened Seattle with numerous sanctions.

The following year he took his case to the Supreme Court and was granted an injunction that allowed him to play and forbade the NBA from taking any further actions. Thus, he paved the way for Darryl Dawkins, Kevin Garnett, Kobe Bryant, and LeBron James to take a chance.

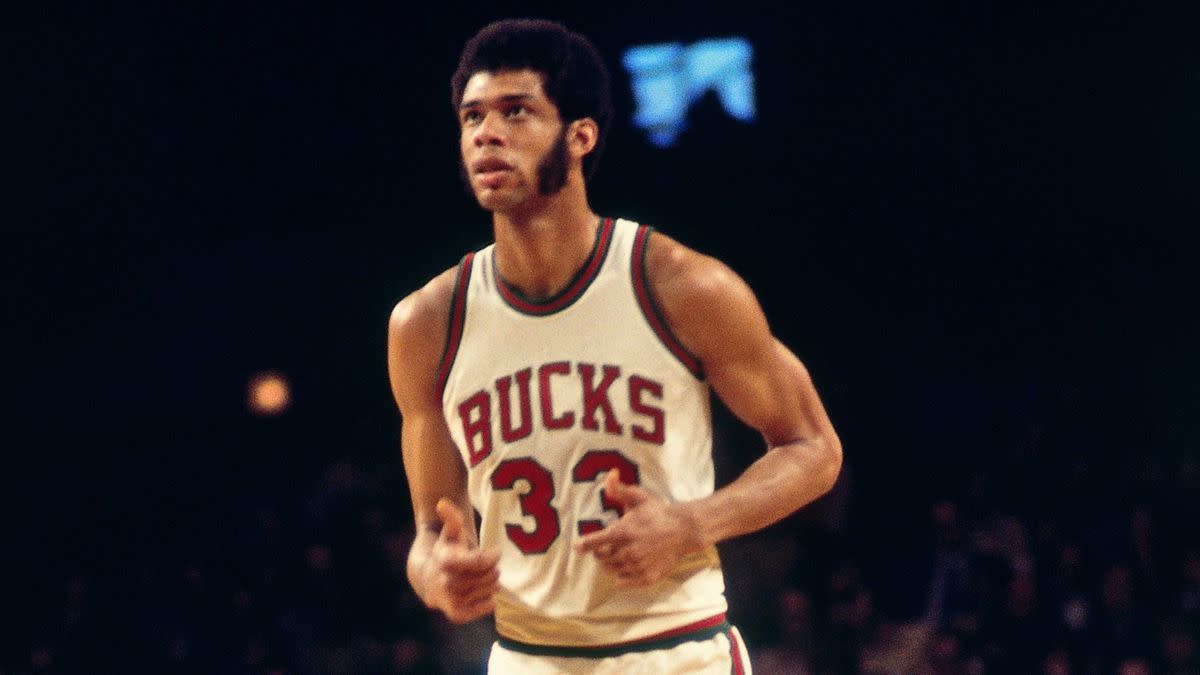

Kareem was a walking billboard for revolution. He had changed his name from Lew Alcindor and converted to Islam while he was spearheading the UCLA dynasty in the late 1960’s and early 1970’s. He supported Muhammad Ali’s refusal to join the Vietnam War efforts and participated in the historic Ali Summit. He boycotted the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City in protest of racial discrimination.

In 1969, he was drafted by the Milwaukee Bucks. Kareem was a fish out of water during that period as an outspoken black athlete in what was still a largely white basketball world particularly in the Midwest. He also defied old adages of black athletes to simply entertain and refused to be manipulated by the white media who portrayed him as an oddity.

“He really refused to play by the kinds of scripts that white reporters and white fans expected of black athletes”, says Dr. Rundsteadler. “There’s this part at the beginning of Chapter 4 where I talk about his interview with Sport Magazine. The journalist had trouble getting a hold of him because Milwaukee didn’t want to push their marquee player too far. They had made it clear that he was ambivalent about the media, particularly the white media.”

There is a famous interview Kareem does with Black Journal in 1971 where he explains himself and his beliefs because he knew that he would at least trust that he would be portrayed more accurately by black media.

His difficulties were evident but he would find a soulmate in Oscar Robertson whom the Bucks had acquired for the 1970-1971 season. The tenacious tandem they formed would lead Milwaukee to 66 wins, a 20 game winning streak, and an NBA title in a sweep over the Baltimore Bullets.

(Courtesy: NBA.com)

What made the pair a match made in heaven was not just for the exploits on the court, but for their shared passion for progress.

Robertson was the man behind free agency in professional basketball.

In 1970, he filed an antitrust lawsuit against the NBA to prevent a merger between the NBA and ABA that would have kept a rule that binded players to a specific team for life. As head of the player’s union, he also advocated for players to have better working conditions, to be properly treated in the case of injury, and to have higher salaries.

He testified before the US Senate in 1971.

(Courtesy: Youtube)

The Supreme Court issued a temporary injunction against the merger until 1976 when it eventually came to fruition. But Robertson, with the help of other black players, unleashed a movement for player empowerment.

That movement that was started by these men has carried over into the present day where LeBron, Chris Paul, Carmelo Anthony, Karl Anthony Towns, CJ Malloum, and countless others have taken up the mantle as it relates to controlling their brands, starting their own companies, and supporting the Black Lives Matter movement.

That spirit of collectivism was on full display when the players famously refused to play games in the Covid protective bubble in Orlando after the police shooting of Jacob Blake in August 2020. In keeping with the players speaking up after the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Amaud Arbery earlier that year.

(Courtesy: Ashley Landis/Getty Images)

(Courtesy: NBA.com)

Dr. Rundstedler sees the landscape of the NBA today when it comes to doing their jobs as attributable to the tireless work of the players of the 1970s.

“Those players from the 70s created the labor conditions and protections that opened up the space for this marketing on the one hand, the massive contracts, the ability to brand yourself, and get a share of the NBA’s profits through the salary cap agreement of the early 1980s, “she says. “Then you have this other side where they pushed for the Reserve Clause to be eliminated and they pushed for guaranteed contracts, better health care, and better support for player injuries. All of which make athletes generally less vulnerable.”

That also extends into activism.

“They can actually say things without fear, without the same level of fear that they had in the late 60s and early 70s. Now, the NBA in the moment of Black Lives Matter has to say now you can put slogans on the back of your shirt because they understand the power of the NBPA and the power of players like LeBron to get their message out.

Black Ball flips the script on conventional wisdom related to the history of the modern NBA. It gives credit long overdue to the trailblazers that made it possible for the hoopsters of today to strut their stuff with agency, authenticity, and security.

Nothing more baller than that.