By: Zachary Draves

It was more than a fight, it was an event. It had all the elements needed for a great sporting spectacle. Drama, anticipation, excitement, and every superlative known to man. Plus there was much more at stake that had global ramifications at a time of heightened fear.

(Courtesy: KEYSTONE-FRANCE/GAMMA-KEYSTONE/GETTY IMAGES)

When Joe Louis and Max Schmeling walked into the ring before 70,000 fans at Yankee Stadium in their second fight on June 22, 1938, the whole world tuned in. Television didn’t exist yet and radio was the go to outlet to absorb sporting excellence in real time, other than being there in person.

(Courtesy: The Ring Magazine/Getty Images)

The world was clouded in a state of upheaval over the rise of totalitarianism that would eventually lead to World War II. That year Adolf Hitler’s Nazi Germany was the personification of that evil and it was the German fighter in Schmeling, who had inadvertently become the poster boy for Hitler’s promotion of his terroristic philosophy of Aryan supremacy.

(Courtesy: HEINRICH HOFFMANN/ULLSTEIN BILD/GETTY IMAGES)

This come on the heels of him upsetting Louis in his first professional loss two years prior at Yankee Stadium in a twelve round knockout. Schmeling’s vicious right hand scorched Louis for much of the fight, due to Schmeling using his right to hit Louis whenever he would leave himself open after swinging his hard hitting left hand and dropping it low.

Also Louis was riding high on his newfound celebrity and was spending a considerable amount of time on the golf course as opposed to training. Whereas, Schmeling had prepared intently for the fight.

It was a moment where the morale swung in the direction of the enemy as Schmeling became a folk hero in Germany.

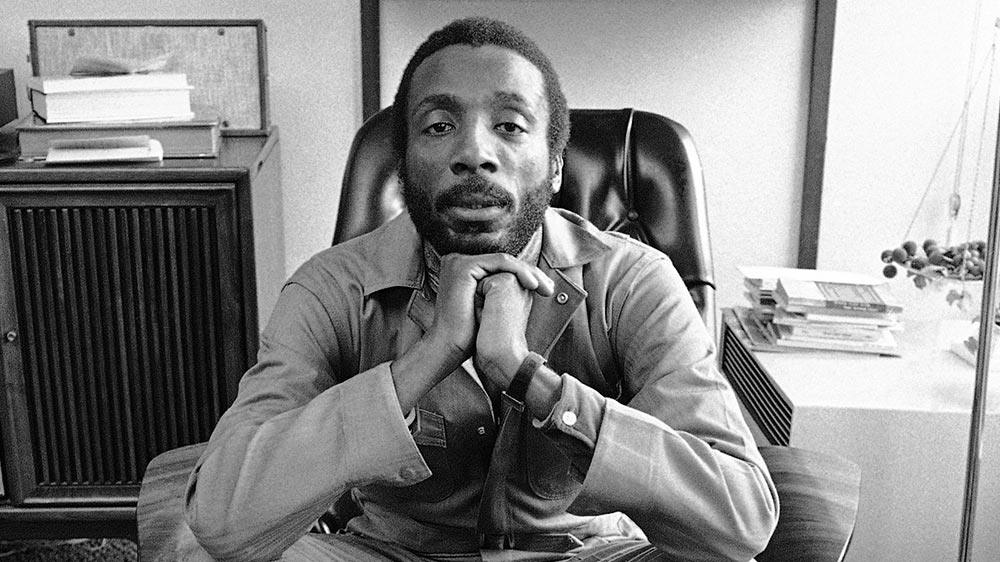

Louis on the other hand was looking to redeem himself. After all, he was just as much of a folk hero, but in particular to Black America. From the time he started fighting professionally in 1934, Louis was a virtual deity to African Americans at a time when Jim Crow and other forms of systemic racism were the law of the land. Every time he would fight, the community would stop what they were doing and were glued to the radio.

When he defeated James Braddock on June 22, 1937 at Chicago’s Comiskey Park to become the first black heavyweight champion since Jack Johnson, black communities all across the country were in a state of sheer euphoria. Celebrations last throughout the night in the streets.

(Courtesy: NY Daily News via Getty Images)

Literary giant Langston Hughes of the Harlem Renaissance cemented the feelings black folks had for Louis as only he could do so with a marvelous tapestry of words:

Each time Joe Louis won a fight in those depression years, even before he became champion, thousands of black Americans on relief or W.P.A., and poor, would throng out into the streets all across the land to march and cheer and yell and cry because of Joe’s one-man triumphs. No one else in the United States has ever had such an effect on Negro emotions—or on mine. I marched and cheered and yelled and cried, too

The symbol of seeing a powerful black men knocking out a white male fighter and defying all the racist stereotypes that had permeated American culture meant something deeply personal. In particular, the title of Heavyweight champion conveyed a herculean notion of strength, resolve, and dignity and for Louis as well as Johnson to hold title was a powerful statement about black masculinity.

The stage was set for a rematch with Schmeling and this time it was for the Heavyweight title. Schmeling had held the title from 1930-1932 after first defeating American fighter Jack Sharkey and then William Stribling, before losing it to Sharkey in a rematch in 1932.

Both fighters knew what it meant to be title holders but this time the tables had turned in the prefight preparations. Louis was training harder than ever and Schmeling was living it up as German’s biggest star.

Going into this fight Louis soon realized that he was carrying the entire weight of a nation on his shoulders and not just his community. In a prefight visit to the White House, President Franklin D. Roosevelt told him “Joe, we need muscles like yours to beat Germany.”

(Courtesy: HA.com)

Even the racism of the time was somewhat put on hold for this one fight because some of those people were in a bit of a catch twenty two. Would they rather have a black champion or a Nazi champion? It turned out at least for one night that virtually the entire nation would be behind a black American fighter in what would become a battle for global supremacy.

According to renowned boxing historian Thomas Mauser, Louis pointed out that “White Americans, even while some of them still were lynching black people in the South, were depending on me to K.O. Germany.”

Schmeling was welcomed to New York City by anti-Nazi protesters and his publicist drew ire when he proclaimed that Schmeling would not only win the fight, but that he would use the prize earnings to build up tanks in Germany.

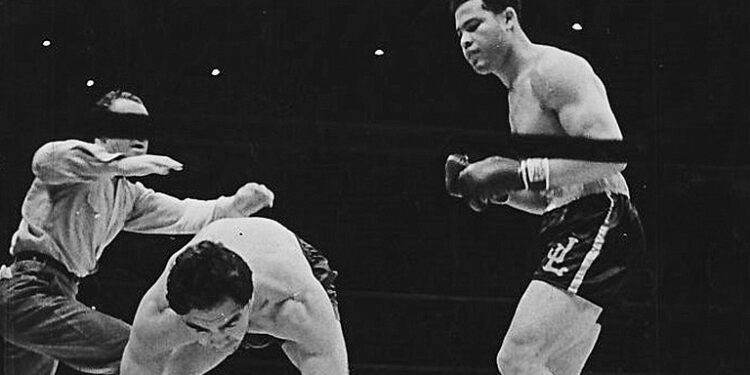

The world held its breath as both men entered the ring. From the time the opening bell rang, it was clear that Louis was the better fighter than he was in the first fight. He came in swarming with a tremendous series of blows that forced Schmeling to the ropes including a body punch that rendered him disoriented.

Louis would knock out Schmeling three times and it was the third knockout that led to Schmeling’s trainer to throw in the towel and the fight was over in two minutes and four seconds.

(Courtesy: Hulton Archive)

Joe Louis had not only maintained the heavyweight title, but he gave America one of its greatest non-military victories over a hostile foreign nation.

The jubilation of his victory was more than palpable. Black and White Americans were ostensibly joined at the hip in nationwide celebrations. For many White Americans it was the first time that they had celebrated the achievements of a Black American.

(Courtesy: NY DAILY NEWS ARCHIVE/GETTY IMAGES)

In the years after, Louis would entertain the Army during World War II and scored a record twenty five title defenses before ending his career in 1951 after a heartbreaking loss to Rocky Marciano at Madison Square Garden.

He would later become a professional golfer and wrestler before encountering financial difficulties stemming from battles with the IRS over backed taxes. Generous spending habits to his family and friends as well as failed business investments hit Louis hard.

In order to generate income, Louis got into wrestling, made appearances on television quiz shows, and was a greeter at Cesar’s Palace in Las Vegas.

Schmeling was reviled by the Nazis and was soon after drafted in the Army as a paratrooper during the war.

Even though he welcomed the Nazis support after his first defeat of Louis, he never joined the Nazi Party. In fact, what eventually led to the deterioration of his relationship with Hitler was his refusal to distance himself from the Jewish community and especially his trainer Joe Jacobs.

Louis and Schmeling would become friends after the end of World War II in 1945. Schmeling even would help Louis out financially during those periods of trying to get out of debt. When Louis died at the age of 66 in 1981, Schmeling was one of the pallbearers at his funeral. Schmeling died in 2005 at the age of 99.

Joe Louis and Max Schmeling were linked forever in more ways than one. But it was that one night eighty five years ago with the world closely monitoring every move and every punch that ultimately forged them together and in the end, all for the better.

NFL

NFL