By: Zachary Draves

There are moments in sports history that go overlooked and leave little trace of existence. So much so that even some of the most enthused sports historians, who make a living by swimming in an ocean of archives and libraries are puzzled when they encounter such lost treasures. One of those moments occurred at the 1972 Munich Olympics. After US sprinters Wayne Collett and Vincent Matthews won gold and silver respectively in the 400 meters, they engaged in what many have come to refer to as the “forgotten protest”.

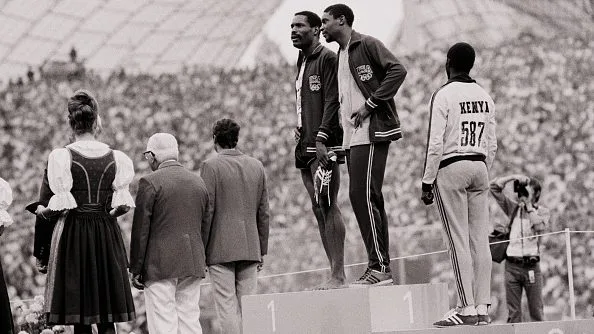

(Courtesy: John Dominis/The LIFE Picture Collection)

During the playing of the national anthem, both broke traditional protocol designed for the medal ceremony. They shared the same podium, casually chatted amongst each other, and turned their backs to the American flag. Meanwhile, Collett was barefoot, had his hands on his hips, and his jacket was open. Matthews was seen occasionally rubbing his chin before folding his arms. As soon as the anthem concluded, they quickly made their way off the field with Collett raising a clinched fist in the air and Matthews twirling his medal around his finger before a loud chorus of boos.

(Courtesy: Associated Press/File 1972)

The IOC immediately dropped the hammer on them and instituted a lifelong ban even while they were allowed to keep their medals. This was at a time when Avery Brundidge, the draconian IOC president with a long track record of Racism and Anti-Semitism known as “Slavery Avery”, was in charge. He later issued a not so subtle threat to Matthews and Collett by saying “if such a performance should happen in the future, the medals will be withheld from the athletes in question.”

Over the last fifty years, both Matthews and Collett have essentially faded from public view. They have never spoken at great length about their actions on the medal stand nor give a full explanation for their reasoning. Thus a debate has ensued about how to properly contextualize these two men and deciding whether or not they actually belong in the same sentence as other athlete activists.

Some have tried to compare Matthews and Collett to the famous 1968 protest by US sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos at the Mexico City Olympics. They raised their clenched black gloved fists in the air in support of racial justice in what became an indelible image that transcended sports. However, the differences are stark starting with the fact that Smith and Carlos were organized and intentional whereas Matthews and Collett were disorganized and spontaneous. But even more stark was that by 1972, there wasn’t a fully intact infrastructure in the form of a social movement that they could latch on compared to Smith and Carlos who were part of the Olympic Project for Human Rights that was organized by then San Jose State University Sociology Professor Dr. Harry Edwards.

“The Civil Rights Movement had lost some of its steam” said Dr. David Wiggins, Professor Emeritus of Sport Studies at George Mason University and the Co-Director of The Center for the Study of Sport and Leisure in Society. “By that time, there wasn’t the real intense black civil rights struggle.”

Four years after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and the collapse of racial justice organizations such as the Southern Christinan Leadership Conference and the Black Panthers due in part to J. Edgar Hoover’s egregious COINTELPRO operation under the FBI, the black freedom struggle was rendered into a state of sporadic chaos. Therefore, the purpose of the protest by Matthews and Collett ringed somewhat confusing.

In Matthews’ memoir My Race Be Won published in 1974, he gives his own version of an explanation though without any real specifics saying “for me, not standing at attention meant that I wasn’t going along with a program dictated by Number One: those John Wayne types, my Country right or wrong.” As for Collett, he provided at least some context with regards to the national anthem when said in an interview with ABC “I couldn’t stand there and sing the words because I don’t believe they’re true. I wish they were. I think we have the potential to have a beautiful country, but I don’t think we do.”

Still there is an increasing level of clamor for more among sports historians.

“I am not so sure what Wayne or Vincent knew what they were doing” said Dr. Wiggins. “I don’t even know if they knew.”

Given the lack of organization, the emptiness of an effective struggle, and the longstanding silence on the part of Matthews and Collett, it is very difficult for them to be inducted into the athlete activist hall of fame that includes Smith, Carlos, Muhammad Ali, Curt Flood, Arthur Ashe, Bill Russell, LeBron James, and Colin Kaepernick to name a few.

However, they deserve a spot in sports history. Their names should be mentioned as a means to explore their intentions and determine whether they do belong in that pantheon of social excellence. A good place to start would be for the IOC to rescind their lifetime ban.

(Courtesy: Hartmut Reeh/picture alliance)

“I agree with that” said Dr. Wiggins. “Hopefully it would garner more attention and generate more discussion.”

Matthews is still living at 74 years old, but still remains in virtual hiding. Collett passed away from cancer in 2010 at the age of 60.

It is past time for these two men to be given their just due. They were amazing athletes who reached the pinnacle and deserve their basic humanity to be recognized. If anything, the present day social movements (i.e. Black Lives Matter) could help to fill the void from fifty years ago and possibly rectify what has become a clear injustice.

NFL

NFL