By: Zachary Draves

It is arguably the most consequential and controversial basketball game in Olympic history.

Against the backdrop of the Cold War, the United States and the Soviet Union duked it out on the hardwood in Munich in the gold medal game fifty years ago. The United States had won 63 straight games in Olympic competition and won seven consecutive gold medals dating back to when basketball made its Olympic debut on the outdoor courts in Berlin in 1936. Meanwhile, the Soviets were beginning to establish themselves a perennial basketball contender utilizing a government run pseudo professional system.

Under that apparatus, they were essentially paid government workers that would receive all sorts of amenities such as the best food, housing, travel, and equipment. As a result, they were able to scurry past the official Olympic rule that forbade the western world defined “professional athlete” from competing. Their disciplined talent and experience, with ages ranging from 20-33, showed signs that they could be on par with the US, whose 1972 team was much younger and considered not to be top notch as compared to years past.

At the time, ametuer basketball in the US was splintering. The Ameatur Athletic Union (AAU) which had long been the sports’ governing body was starting to lose its clout. They and the NCAA were at odds over who would control the future of ameatur basketball and what the 1972 team should represent. The NCAA wanted UCLA’s John Wooden or North Carolina’s Dean Smith to take the reins as Head Coach. The AAU wanted the then gravely ill Adolph Rupp of Kentucky, but it was the middle ground choice of Oklahoma A&M’s Henry (Hank) Iba, who helped guide the 1964 and 1968 US teams to gold, who got the job.

In the meantime, the asendence of professional basketball was compromising the ameatur ranks. Top players were seeking out the NBA and ABA, avoiding the Olympics altogether. Others such as UCLA’s Bill Walton, who along with Coach Wooden helped spearhead the Bruin dynasty in the early 1970s, declined to play. Some suggest that because he was active in the anti-Vietnam War movement at the time, he chose not to play for those particular political reasons. But Walton himself said that a major reason was a negative experience he had at the 1970 World Championships, which he described to ESPN in 2004.

“For the first time in my life, I was exposed to negative coaching and the berating of players and the foul language and the threatening of people who didn’t perform” he said.

He also felt that he didn’t need to try out but Coach Iba made it clear that he needed to go through the process as everyone else. Ultimately, Walton wasn’t heading to Munich nor was Coach Wooden. Given that they were the best player and coach at the collegiate level, could they have made a difference in the hopes for the US team?

“Wooden not Iba should have been the coach,” said Dr. Robert Edelman, Professor of Russian History and the History of Sport at the University of California, San Diego. “Walton would have played.”

In the end, the US sent its youngest team ever to Munich with some concerned that they didn’t have all that it took.

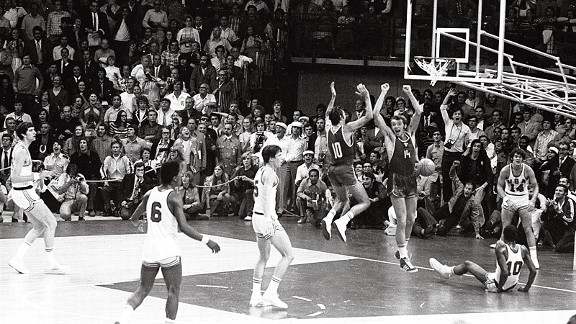

(Courtesy: USA Basketball)

Nevertheless, the US was expected to steamroll its way to an eighth consecutive gold medal. The gold medal game began at 11:45pm in Germany in order to accommodate American television. Throughout the game, the Soviets were in control as they took advantage of the US team’s unusually slow pace of play. At the time, the American game was becoming faster and up tempo, but US Head Coach Hank Iba had them play at an even keel at both ends, which worked towards the betterment of the Soviets.

(Courtesy: Tony Duffy/Getty Images)

With 10 minutes left in the game, the Soviets had a 10 point lead. It was at that moment that the US players took manners in their own hands as they went against Coach Iba’s original plan and started to press, run, and scramble. Little by little, the US started to claw their way and before they knew it with forty seconds left they trailed by one 49-48.

In the remaining moments, American guard Doug Collins stole an inbounds pass, drove to the basket, and was fouled hard. He shrugged it off to make his way to the foul line and converted both free throws, which can be described as possibly the most pressure packed shots ever taken in the history of basketball. With three seconds left, the US led 50-49 and were well on their way to winning the gold medal, until chaos arose.

After the Soviets inbounded the ball, their coaches began to complain to the referees that they weren’t granted a timeout they had requested after Collins first foul shot. As a result play halted with one second remaining and left both sides in a state of dismay. According to international basketball rules at the time, a timeout could only be granted when the clock was halted, which in this case was before or after Collins first foul shot. The coach would press a hand held electric buzzer requesting a timeout, but the scorer’s table missed it. Once the referee handed the ball to Collins for the second foul shot, the ball was in play and a timeout couldn’t be granted.

(Courtesy: Rich Clarkson/Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images)

As both sides went to their benches to regroup, television cameras caught Dr. R. William Jones, the British born co-founder of FIBA, held up three fingers indicating to the scorer’s table that three seconds ought to be put back on the clock. Even though he had no official jurisdiction over the game, they ultimately acquiesced to his request.

The Soviets were given the opportunity to inbound the ball for a second time. Once they did, the horn sounded, which most had interpreted to be the end of the game, because there was theoretically one second left and the US had a one point lead 50-49. The US players and coaches began to celebrate on the court thinking they had pulled off a remarkable comeback to win the gold medal. But their moment of sunshine was quickly darkened.

(Courtesy: AFP/Getty Images)

It turned out the clock had been reset at fifty seconds and not three seconds. The horn that had been blasted was to indicate that problem, not a signal that the game was over. So in a state of utter confusion and frustration, the Soviets were given a chance to inbound the ball for the third time. Soviet forward Ivan Edeshko was to inbound the ball and US forward Tom McMillian was guarding him along the baseline.

McMillian would later say that the referee, who was Romanian and didn’t speak any English, was instructing him to step back from the line by pointing at his feet. Even though he said that the rules at the time indicated that a defender could be against the line just as long as it doesn’t preclude the inbounding player from backing up. In the heat of the moment and not wanting to risk a technical foul, McMillian took a couple steps back.

Therefore, Edeshko was able to throw the full length of the court with poetic precision to find Soviet center Alexander Belov at the other side. He caught the pass between two American defenders, Jim Forbes and Kevin Joyce, who lost position leaving Belov all alone to lay the ball up and give the Soviets the 51-50 victory in stunning fashion.

(Courtesy: Rich Clarkson/Time & Life Pictures/Getty Image)

Soon after, the US team officially protested the outcome of the game. An investigation was conducted by FIBA and the vote was purely along Cold War lines 3-2. The Communist bloc countries of Cuba, Poland, and Hungary voted in favor of the Soviets and Italy and Puerto Rico voted for the Americans.

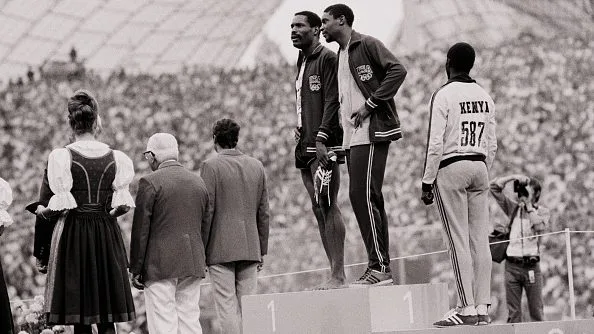

(Courtesy: Bettman via Getty Images)

The Soviets enthusiastically took the gold, but the Americans took the unprecedented step of refusing to accept the silver medal. During the medal ceremony, the podium reserved for the Americans was left empty. To this day, the silver medals remain locked away at the Olympic Museum in Lausanne, Switzerland and there is no indication that any of the US players still around will claim them.

(Courtesy: Bettmann/Corbis)

Among those are team captain Kenny Davis, who was an All American at Georgetown College in Kentucky. He was the orchestrator of the effort to not accept the medals and says that the team was given a specific amount of time after the official FIBA ruling on the outcome of the game to decide what happens next.

“We had 14 hours to think and once that decision was handed down, we automatically decided to not accept the silver medal,” he said.

Davis makes no qualms about who the scapegoat was for the fiasco that ensued and that was none other than Dr. William Jones who ordered the scorers table to put those three seconds back up.

“He had no authority to do what he did,” he said. “Obviously he was the main culprit.”

In the years since, Davis says that he has no regrets about declining the silver medal. He even put a specific provision in his will stating that his wife and children may not accept the medal after his passing.

“We put a will together and I asked the lawyer if it were Ok to put it in there,” he said. “I just felt like it was the best decision.”

But even in the midst of his and his teammates resentment, he at least was able to acknowledge some perspective considering that they were able to go home whereas the 11 Isreali athletes who were murdered by terrorists in the massacre on September 5 were not.

“We had careers and families,” he said. “To compare what happened to us to what happened to them is not right.”

This game with all its controversy represented so many things. It was the first inclination that the rest of the world had begun to catch up to the United States and that title of basketballI supremacy was up for grabs. Thus a global basketball renaissance was unleashed and has only gotten stronger.

It has also festered an intense and ongoing debate fifty years on about who the actual winner is. What tends to happen is that there is the US and the Soviets in their respective corners and neither side acknowledging any semblance of nuance.

When US players say that were cheated, Dr. Edelman begs to differ and takes a broader stance.

“Cheated means a conspiracy. A series of errors conspired to the result.” he said. “The US won the Cold War. Can they not admit there were some situations in which the Soviets (the team was not exclusively Russian) did well?

As for Davis, he maintains his position that it was the US that won fair and square.

“Under the rules of the game of basketball, we won the gold medal,” said Davis. “We followed them. These (Soviet) players in the back of their minds know they lost the game.”

Will we ever see a thorough resolvement on the matter that would satisfy all? Emphatically no. Both sides will remain confined to their positions and will not bend, but one thing everyone can agree on is that the legacy of this game is so rich with history that it brings out such vital discussions around the intersection of sports and geopolitics.

And all it took was three seconds.

NFL

NFL