By: Zachary Draves

The year was 1968. A year of tremendous upheaval and turmoil, not entirely unlike what the world is experiencing now. It seemed as if it was a never-ending ball of confusion with the future of America looking bleaker by the minute.

An increasingly unpopular and unwinnable war in Vietnam was escalating, President Lyndon B. Johnson declared he would not seek out a second term, the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Bobby Kennedy destroyed any sense of hope and optimism, and the Democratic National Convention in Chicago descended into chaos both inside and outside the convention hall.

In these circumstances and perhaps for the first time since World War II, sport was no longer just a space of simple pleasure and escapism. Something that was made crystal clear the year prior, when Muhammad Ali refused induction into the United States Armed Forces on religious grounds and was stripped of his title as Heavyweight Champion of the world.

Thus, unleashing a new era of athlete activism.

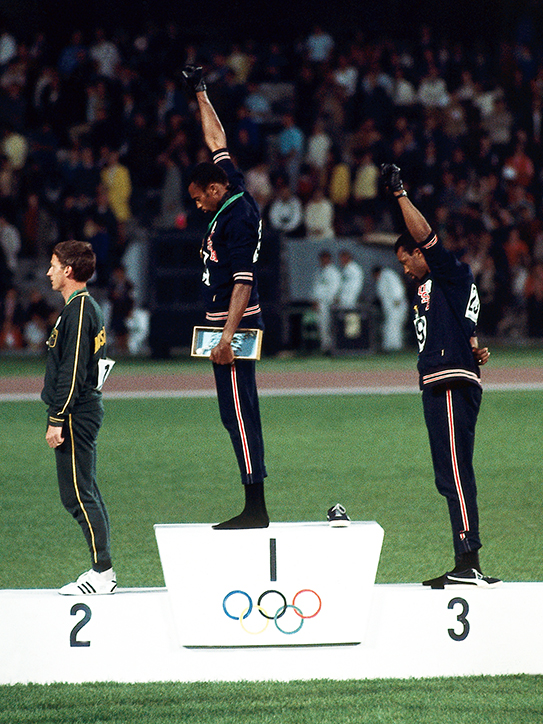

As Ali’s predicament became front and center, a group of future Olympians were in the midst of figuring out how to cultivate themselves as more than athletes in the same fashion in the lead up to the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City. They were Tommie Smith and John Carlos, two sprinters at San Jose State University in San Jose, California.

(Courtesy: Neil Leifer)

They along with teammates Lee Evans, Wyomia Tyus, and others were very much caught up in the chaos surrounding them and there to remind them of the power they had to effect change was former college athlete turned sociology professor Dr. Harry Edwards, who would go on to pioneer a new field of academy study, the sociology of sport.

One year earlier, Dr. Edwards formed the Olympic Project for Human Rights, which put forward some aggressive demands about racial and social justice and if none of these demands were met, then black athletes would boycott the games.

(Courtesy: Corbis via Getty Images)

Among the demands included more black coaches, the restoration of Muhammad Ali’s title, the banishment of Apartheid nations South Africa and Rhodesia, and the ousting of the International Olympic Committee president Avery Brundage.

Brundage was a notorious racist and anti-Semite who was instrumental in granting Adolf Hitler the 1936 Olympics in Berlin. He also owned a prominent country club in Santa Barbara, California that had a policy in effect that explicitly prohibited blacks and Jews from becoming members.

Some athletes were reluctant to the idea of not going to Mexico City in protest and backed out of a proposed boycott of a mid-winter meet at the New York Athletic Club to call out racist hiring practices. Debate raged over the summer about what to do. Ultimately what was decided was that black athletes would go to Mexico City and while there they would make a statement about racism in America however they saw fit.

Some chose to stay home in protest including UCLA basketball phenom Lew Alcindor, later Kareem Abdul Jabbar along with teammates Lucius Allen and Mike Warren.

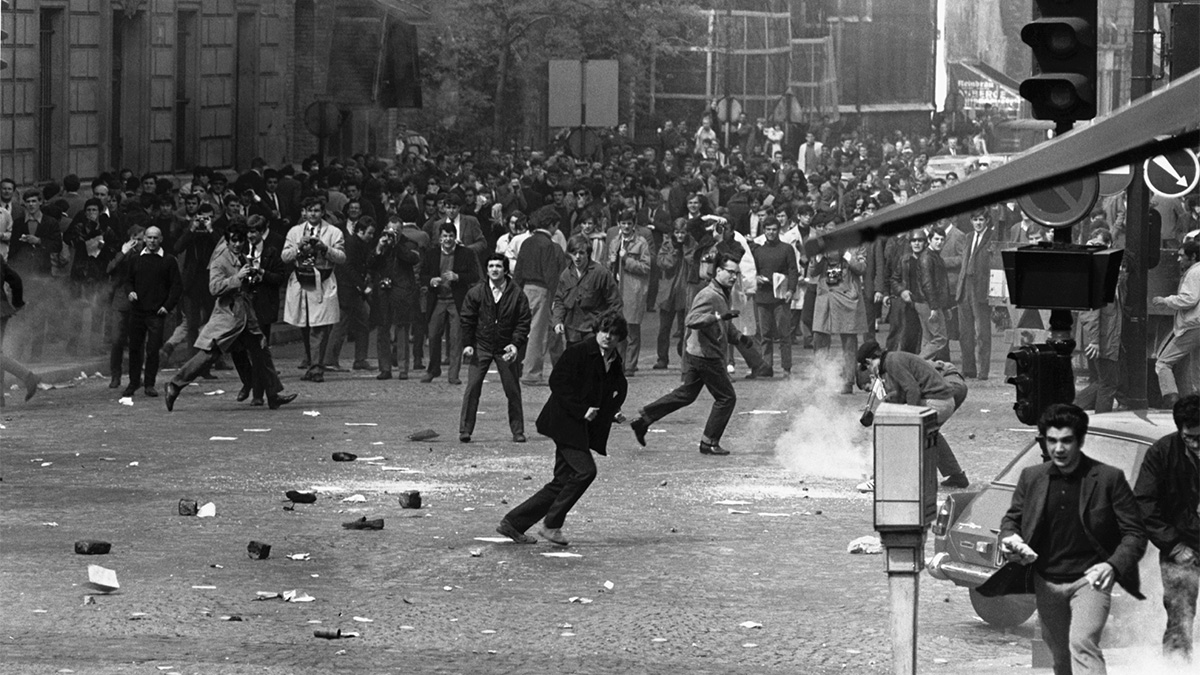

Little did the athletes know that they were leaving one chaotic country for another. Just days leading up to the opening ceremonies, hundreds of students protesting the games were massacred by the repressive Mexican government in what became known as the Tlatelolco Massacre.

(Courtesy: Corbis Via Getty Images)

Nearly 400 people died and over 1,000 were injured.

The Olympic organizers went above and beyond the call of window dressing to hide and conceal the carnage as much as possible in order to present the games as a space of goodwill and sportsmanship, even though that wasn’t possible, especially under the leadership of Avery Brundidge.

Famed sports journalist Robert Lipsyte covered these games and was struck by the degree of window dressing when he got there.

“I got there fairly early and was friendly with one of the tourist guides,” he said. “She took me to a plaza in Mexico City where the cobblestones had been power hosed. There were blood spots. On the ride from the airport to the Olympic Village, I was struck by how gleamingly white the tunnel from the airport to the Olympic Village was because everything had been whitewashed.”

The ample time was there to make a profound social statement and on October 16, Smith and Carlos did just that.

After Smith won the gold and Carlos the bronze in the 200-meter final, they stood on top of the victory podium, and during the playing of the national anthem, they bowed their heads and raised a black-gloved fist into the air.

(Courtesy: AFP/Getty Images)

It was a strong silent statement about the need for America to live up to its promises of justice and equality and was done with protocol.

Smith raised his right arm and Carlos his left arm to form a “U” for unity. They both took their shoes off and wore black socks to symbolize black poverty. Smith wore beads around his neck to honor those who were killed by lynching. Carlos opened up his jacket in solidarity for working people of all backgrounds. Each wore a button that read the Olympic Project for Human Rights.

Joining alongside them was silver medalist Peter Norman of Australia. He had requested prior to the medal ceremony to wear one of the buttons in solidarity.

“I looked at it from the stands and said,” Is that it?” said Lipsyte. “What they did seem to me was one of the most humane gestures of that year. They just quietly raised to black-gloved fists in the air.”

Afterwards, Smith and Carlos were hit with a barrage of boos, racist slurs, and garbage being thrown from the stands. They were allowed to keep their medals but were subsequently suspended by the US Olympic Committee after the IOC threatened to suspend the entire track and field team if they weren’t immediately given the boot.

Both men came home as pariahs and their lives suffered immensely in the years that followed which including financial troubles and death threats.

That moment crystalized a moment in time, but it wasn’t confined by time.

55 years later, the impact is still being felt by today’s generation of athlete activists who look to this moment for inspiration.

Among those is Olympic hammer thrower Gwen Berry who famously took part in protests of racial injustice at the 2019 Pan American Games and the 2021 US Olympic Trials.

“It impacted me pretty significantly,” she said. “It is the best way I knew how to protest and to give off my sentiment of unity.”

Growing up in East St. Louis, Illinois she recalls seeing that image in libraries and fast forward as an adult she never thought she would be in a position to take a stand until her heart spoke first.

“It was really something that came from the heart,” she said. “To be able to take that action, it wasn’t something that I thought of doing, it felt something in my soul and I felt that I had to take the stand.”

She has also considered Dr. Carlos as a mentor who was there for her.

History has a unique way of capturing and telling stories from varying degrees. Oftentimes when it pertains to the intersection of sport and society, there are ongoing debates about who is more impactful.

But when looking at the actions by men of courage in Mexico City, Lipstye has insight into their greater legacy.

“Smith and Carlos were on a tightrope without a safety net” he said. “But those guys were believers. Harry (Edwards), Smith, and Carlos believed that sports were important and a crucible for character.”

55 years onward.