By: Zachary Draves

The outpouring of loving tributes to Jim Brown in light of his passing on Friday at the age of 87 are certainly warranted. Everything he did in terms of his athleticism, acting, and activism was revolutionary and by and large for the better.

But just like the rest of us, he was flawed.

He was a man of unrelenting ambition who wasn’t the least bit shy to bring the pot to a boil every chance he could get, particularly at a time in American history when that was needed. At the height of the black freedom struggle in the 1960’s, Brown was the symbolic and substantive embodiment of the defiant black man both on and off the gridiron.

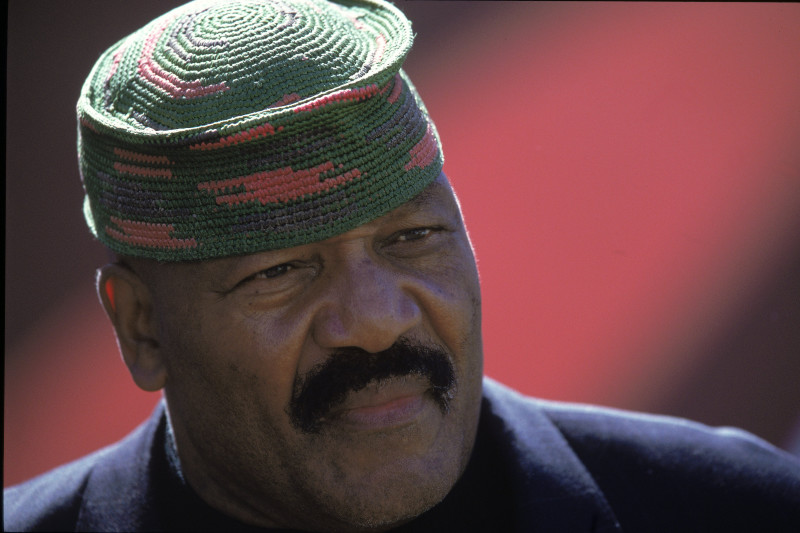

(Courtesy: Associated Press)

When it came to football, his blistering speed, explosive dynamism, and unmeasured aggression helped redefine the game. He ultimately set the standard for what it meant to be a running back and therefore many have categorized him as the best to ever do it.

The hardware he collected said it all. Three MVPs and eight times leading the league in rushing yards.

Every time he ran with the ball and pulverized his way through the defense, he was sending a powerful statement about black manhood and excellence that while he may be knocked down from time to time, he would always get back up.

Those same traits can be made for his days on the lacrosse field at Syracuse. He played with the same intensity and passion, which helped him win three consecutive national championships from 1957-1959. He also scored a nation high 43 goals in his senior year and was a three time All American.

In addition, his superb talent helped spur a rule change where players had to run in constant motion while carrying the ball as opposed to what Brown did which was to hold the stick close to the body. Much like Kareem Abdul Jabbar, Simone Biles, Surya Bonaley, and Serena Williams black athletes whose innovative exploits lead to rule changes aimed at neutralizing them.

However, Brown never wavered and did whatever it took to stay true to his convictions.

That mentality did wonders for him as an actor and activist.

His roles in classics such as The Dirty Dozen and 100 Rifles where he worked with the likes of Donald Sutherland, Burt Reynolds, and Raquel Welch, portrayed a strong powerful black man, completely antagonistic to the longstanding and objectifying stereotypes of black people in mass media.

As an activist, he made it clear from the beginning that he was to be taken seriously.

He was the chief organizer of the Ali Summit in 1967 which brought in Bill Russell, Kareem Abdul Jabbar (then Lew Alcindor), and community leaders to Cleveland to show support for Muhammad Ali after his refusal to join the armed forces in the Vietnam War.

(Courtesy: Robert Abbott Sengstacke/Getty Images)

In 1968, he established the Negro Industrial and Economic Union which advocated for black communities taking control over their economic and social matters.

(Courtesy: Associaed Press)

In 1988, Brown established the Amer-I-Can program, which works to change the lives of gang members and those who are incarcerated.

(Courtesy: Amer-I-Can Foundation)

All these feats in these areas are to be commended and celebrated. But at the same time if we are to be honest about Brown’s life, we also have to acknowledge his troubled side.

Beginning in the mid to late 60’s, Brown began developing a reputation for being violent, especially towards women. From 1965-2002, he was charged with domestic violence, assault with the intent to committ murder, rape, battery, and vandalism.

In most of these cases, he seemed to not take any personal accountability for his actions nor willing to let go of the toxic masculinity that he wholeheartedly embraced. Instead he would sometimes say that he was being targeted by the system because of his activism.

The problem is that while that may have made sense in the context of the surveillance state created by J. Edger Hoover’s FBI and COINTELPRO operation which cracked down on the social movements of the 1960’s, it does not hold true when these acts of violence occurred in the 1970s, 1980s, 1990s, and early 2000s.

While he was never found guilty in these cases, he was fined, put on probation, sent to domestic violence counseling, and sent to jail for refusing to comply with a court order to do 400 hours of community service. In other words, he still had to do his part to make amends for his behavior.

Plus it was a bit hypocritical of him to educate gang members and incarcerated individuals about taking responsibility for one’s actions, don’t make excuses, and commit to making a change, when many times he didn’t do that himself. That’s not to take away from the transformational and necessary work of Amer-I-Can, but it is to point out Brown’s inconsistency.

Those same greivances can be applied to examining his later support for former President Donald Trump, which puzzled many. The idea that a man who was football’s equivalent to Malcolm X could support a guy like Trump with his recorded history of racism didn’t seem to register. But when you look at the one commonality they share which is toxic masculinity, it makes complete sense.

(Courtesy: Harry How/Getty Images)

The point being is a life has many chapters.

Jim Brown was a man full of contradictions. A man who fulfilled his obligations as a sportsman and but not always as a social change agent due to his personal life.

So if we are gonna put his life into its proper context we have to talk about the good, bad, and ugly.