By Bill Carroll

Kenny Washington, born Kenneth Stanley Washington, August 31, 1918, was the son of Edgar Hughes “Blue” Washington, who was a boxer in his youth, a Negro league baseball player, with multiple teams and later, an actor. The mother of Kenny Washington, Marion Lenán-Washington was from Kingston, Jamaica, and only age 16, at the time of the betrothal. “Blue was a man who enjoyed a good time, more than marital responsibilities, after only two years his marriage to Marion Lenán crumbled.

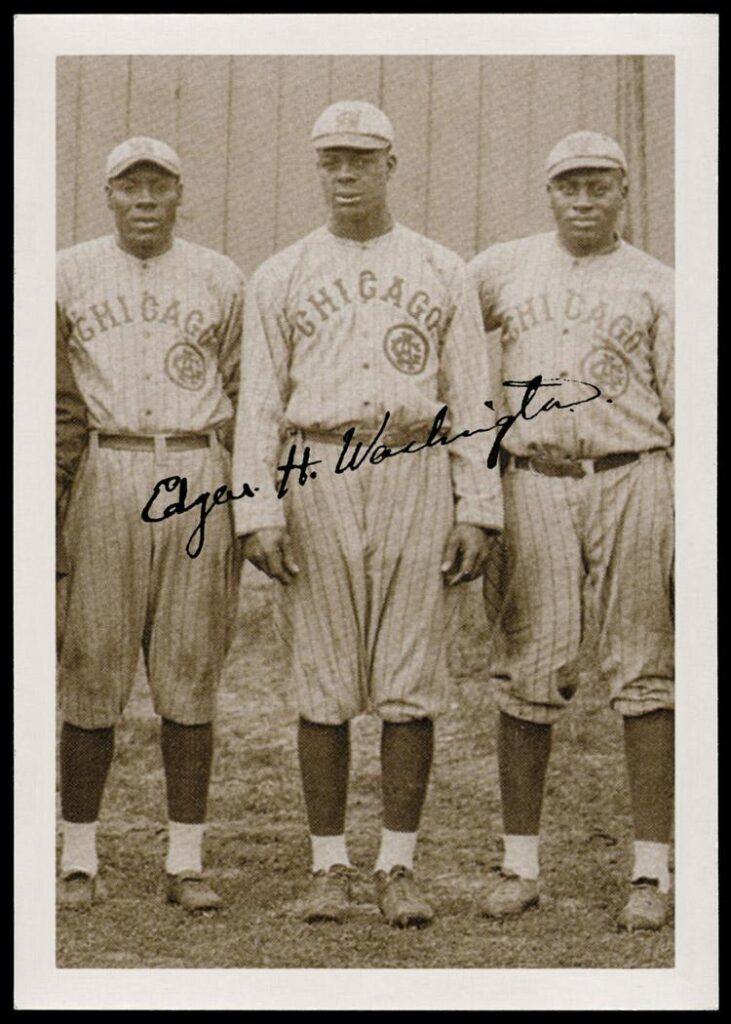

“Blue” Washington was born February 12, 1898 in Los Angeles, California, as Edgar Hughes Washington. In his youth he was a close friend of Frank Capra. In fact, his nickname ‘Blue’ came from Capra. He played professional baseball in the 1910s and 1920s. Later, perhaps due to his connection to Capra and the director’s connections, Washington found his way to Hollywood. Which, at that time, was only marginally more accepting of Black talent than the all-White major leagues. Many of his roles were uncredited, but he was most noted for, There It Is (1928), Beggars of Life (1928) and Haunted Gold (1932).

Kenny Washington was raised in the relatively, diverse environs of Lincoln Heights, Los Angeles. At the time, his father, was not yet, working steadily as an actor. Edgar ‘Blue’ Washington, while pitching for Lonnie Goodwin’s, semiprofessional Los Angeles White Sox, caught the eye of , Rube Foster and other, better teams, leading to the next stop in his career, as a pitcher, in the starting rotation, with Rube Foster’s Chicago American Giants. After a few years in the sandlots, he even played first base for a newly-born version of the Kansas City Monarchs

“The Father of Black Baseball”, Rube Foster, discovered Washington during the Chicago American Giants’ 1916 West Coast spring-training schedule. ‘Blue’ was invited to travel with and pitch for the legendary team, boasting a roster, comparable to the New York Yankees’ Murderers’ Row. Babe Ruth was still a member of the Boston Red Sox, known, primarily for pitching. This Giants team produced three National Baseball Hall of Famers: Pete Hill, Pop Lloyd, and of course Foster.

During Washington’s time with American Giants, he pitched in seven games, with three victories and a loss, versus White teams from Pacific Coast and Northwestern Leagues.13 “Ed Washington,” as he was called, ruled the mound with an unorthodox pitching style. His Giants’ debut, a March 31, 1916, was against the Portland Beavers, in Sacramento, the Chicago Defender April 8th, 1916, reported the action:

“Inability to hit the offerings of Ed Washington, {an}18-year-old pitching phenom picked up in Los Angeles by ‘Rube’ Foster and the poor fielding of Shortstop Ward were two things that beat Portland again Friday, the American Giants walking off with the second game by a 5 to 2 score. With a deceiving underhanded delivery and some shoots a sight more deceiving than his delivery.

Washington tolled on the mound to good effect. Inning after inning Mack [Walter “Judge” McCredie] sent his heavy hitters to the plate, only to have the majority of them return to their starting point. Portland’s two runs were not primarily the fault of the youthful black hurler. They were both made after Second Baseman Bauchman had allowed two men on bases by boots on easy chances. … Although Portland got men on in the second and third, they were unable to get around, due to the effective pitching of Washington.”14

The few opportunities to play a role that allowed a performer to maintain their dignity were extremely few and served as a poignant counterpoint to the vast majority of available roles. While some actors like: Lincoln Theodore Monroe Andrew Perry AKA “Stepin Fetchit”, Dudley Dickerson, Willie “Sleep n’ Eat” Best and Mantan Moreland, worked steadily and “Stepin Fetchit” was the first Black actor to achieve one million dollars in career earnings, but it was a brief and rare occurrence when any Black actor could slip free of the snare of being demeaning, comic relief.

As a six-year-old, Kenny Washington was, often deposited, at early-morning mass, at the urging of an Italian woman neighbor. His father, Edgar (Blue) Washington, was as variable as the west wind, playing Negro leagues baseball, between bit-player and sidekick, acting jobs in Hollywood. He collected his pay, disappeared until the good times stopped, only to return, to begin the cycle again.

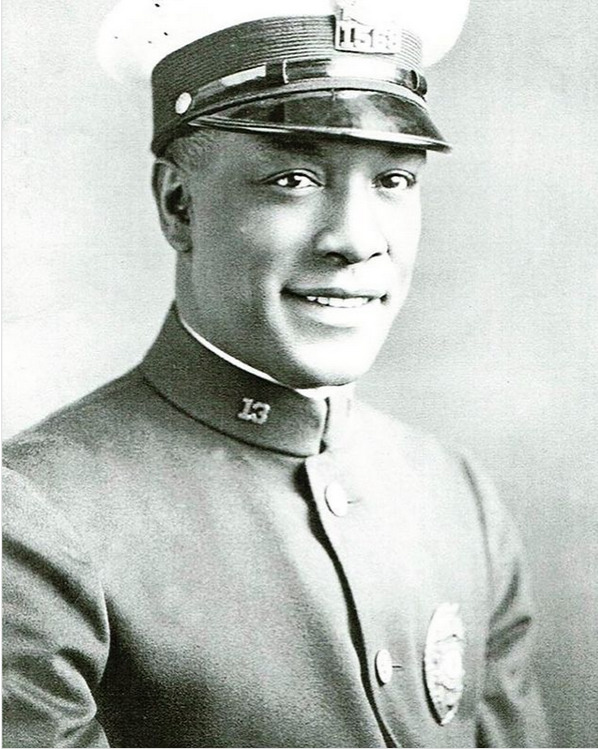

Kenny Washington, like his father, was a star in multiple sports, at Los Angeles’, Abraham Lincoln High School, he starred in baseball and football. He was raised by his grandmother Susie Washington, he had an uncle Roscoe Conkling “Rocky” Washington, in 1940, was made, the first Black uniformed lieutenant in the Los Angeles Police Department.

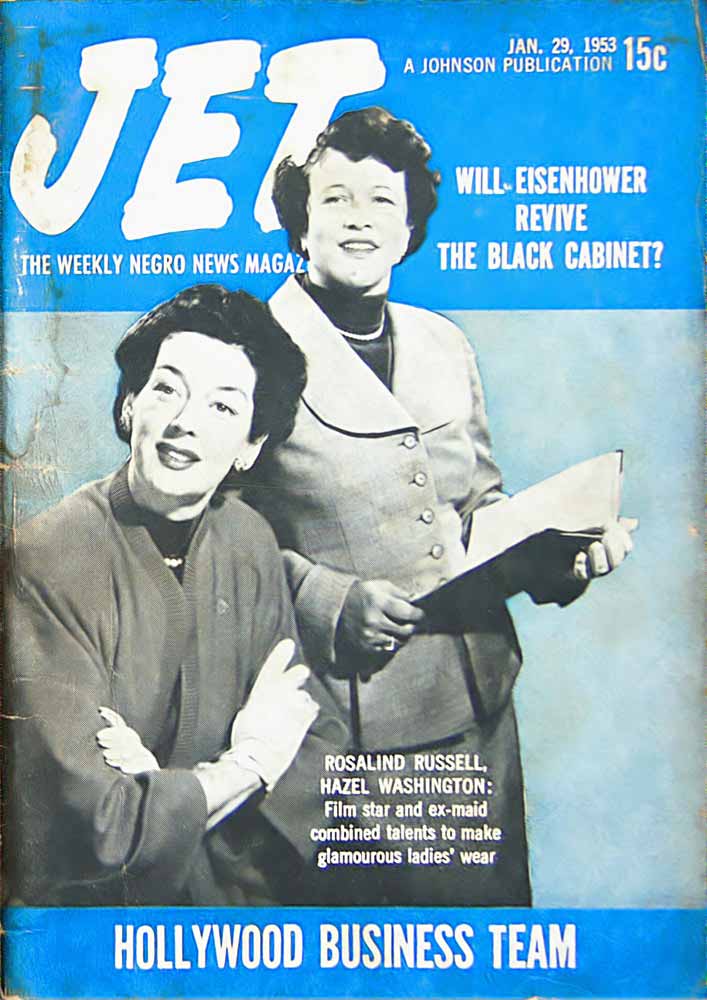

His aunt Hazel Anderson-Washington, married to “Rocky” Washington, was a close friend and secretary of actress Claudette Colbert and went into business with Rosalind Russell. Hazel Anderson-Washington was a leather-artisan, clothing designer, as well as one of the first, Black, licensed cosmetologists, in Los Angeles.

Kenny Washington had many examples of how to thrive, despite the crushing hand of racism on your throat. He showed athletic gifts early. Kenny Washington broke both knees in a bicycle accident at age 10, but, still Kenny Washington led Lincoln High School to a City Section baseball title as a junior (he had a home run in the championship game) before leading his school to a football title that fall.

“I heard a lot of tales about him, and I didn’t believe it at first,” his grandson, Kirk Washington, said. “But then you talk to people who saw him play and it was all true.”

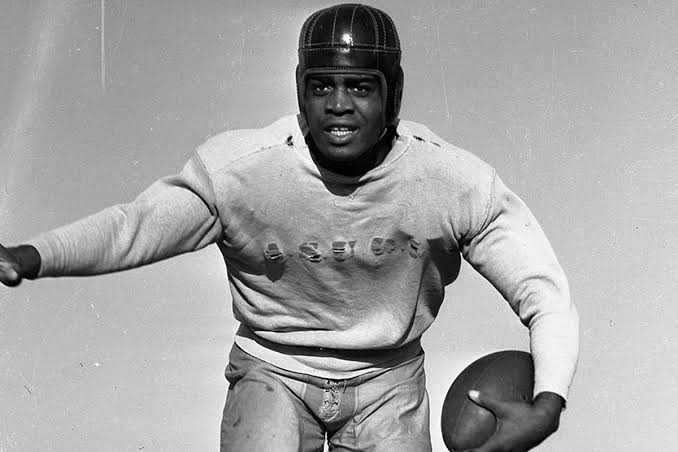

Kenny Washington drew the rapt attention of Negro League and few major league scouts after batting .454 and .350 for the Bruins in 1937 and 1938. Despite his obvious talent on the diamond, it was on the gridiron that Kenny Washington was a national figure. The offensive engine of a relatively integrated roster, for its era, Kenny Washington was a single-wing tailback, his playing style was similar to a modern-day quarterback in a Veer option-style offense. He was the team’s field general, and the Los Angeles Times took to calling him “General Washington.”

When Robinson was at Pasadena JC, “[Washington] was a guy who would go and watch [Robinson] play and come back and tell the UCLA coaches “We have to have him, this is the guy we have to have,” Dan Taylor , author of “Walking Alone: The Untold Journey of Football Pioneer Kenny Washington” said.

Kenny Washington realized that he couldn’t count on Blue. He instead credited two others with raising him: one was his grandmother Susie, custodian at the grammar school, known for aiding the daughters of her Italian neighbors, regarding their daughter’s gentlemen callers; with her knowledge of all the local schoolboys.

His uncle Roscoe C. “Rocky” Washington, who joined the LAPD in 1925. In 1940, he became the first Black Lieutenant and Watch Commander, with both the Black community and the force, his reputation was sterling, as one of department’s most respected lieutenants. In a striking coincidence, his uncle “Rocky” Washington was promoted to sergeant, and later lieutenant, while assigned to precinct 13. 13 was also the number that Kenny Washington made famous.

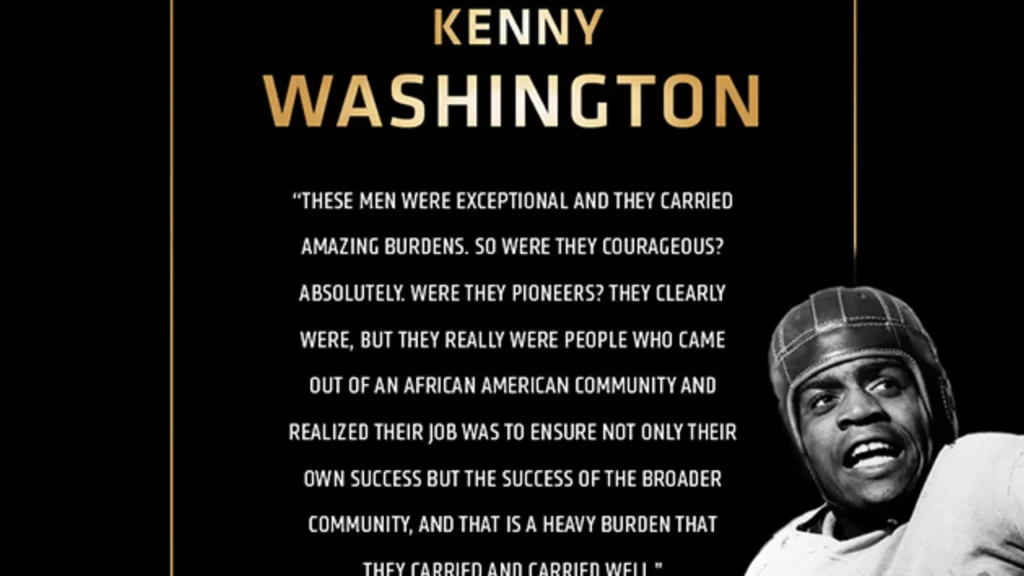

Kenny Washington: The Best Of Times, And The Worst Of Times

“I had a Black principal in my grammar school when I was a kid,” Strode would recall. “On the Pacific Coast there wasn’t anything we couldn’t do. As we got out of the L.A. area we found these racial tensions. Hell, we thought we were White.” “When I met Kenny, I swear he was nothing but a nice Italian kid,” Strode wrote in his 1990 memoir, Goal Dust. “He had an accent that was half-Italian.”

While Jackie Robinson and Kenny Washington had several, obvious, external similarities: they grew up in integrated parts of Los Angeles County, just six miles apart, were stars and champions in multiple sports and both were courageous pioneers, but the were never close.

Kenny Washington was, largely embraced at Westwood, but Robinson was seen as a gifted interloper. His status as a Pasadena JC transfer may have been partially responsible, some was likely due to a Pasadena run-in with a motorcycle policeman, September 1939 immediately before he arrived at UCLA.

The other major point of divergence in the paths of Jackie Robinson and Kenny Washington, centers around Scott United Methodist Church and, a then, 25-year-old Reverend Karl Downs. From 1938 to 1943 Dr. Karl E. Downs was pastor of Scott Methodist Church in Pasadena, California, becoming the Robinson’s pastor. Jackie had been hanging with a tough crowd. The pastor became a father figure to Robinson, rekindled his religious life, got him out of the streets and bolstered his sense of racial pride.

42 Today: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy, edited by Michael G. Long, also takes a closer look at this pivotal and important friend and mentor-ship: “Further, Robinson discovered that he could share his own personal predicaments and struggles with his thoughtful new pastor. Robinson was torn by his mother’s menial work and his own inability to support her financially.

This though it is not stated, deeply affected his sense of manhood as he thought about his athleticism and his desire to support his mother. Because of Downs’s pastoral counseling, as [Arnold] Rampersad notes, Robinson began to experience a “measure of emotional and spiritual poise such as he had never known.” Downs’s counsel, coupled with his ability to organize constructive youth programming, encouraged Jackie to see the church as a community servant.“

Having a gun pulled on him after a White motorist called him and his friends “N-ggers”, marked Jackie as potential trouble at UCLA. “It was pretty hard to shake off,” Robinson told Rampersad. By way of contrast, Kenny Washington (who had two uncles on the police force) was a favorite. With the fans and especially among White journalists. As Claude Newman wrote in the Sun Valley Times years later, “With such men [as Washington] there are no racial problems. Would that there would be more like him.”

Kenny Washington was the UCLA Bruins’ first consensus All-American in the history of their football program, in 1939. That same year he earned the Douglas Fairbanks Trophy for being named the most outstanding player in college football. Kenny Washington totaled 9,975 yards rushing in his collegiate career, a record that stood at UCLA for 56 years According to Time magazine’s coverage of the 1940 College All-Star Game, Kenny Washington was “Considered by West Coast fans the most brilliant player in the U. S. last year.” However, he was voted second-team All-American and was not invited to that year’s East-West Shrine Game.

It may be that the founder of the East-West Shrine Game, Orin Ercel “Babe” Hollingbery, the same coach that had screamed racial epithets at Kenny Washington, during games versus Washington State, exerted his influence to exclude him. The Black press and White, West Coast media outlets, correctly, blamed racial discrimination for the snub.

After graduation, George Halas, who had coached him in the All-Star Game, attempted to sign Kenny Washington to the Chicago Bears, but demurred when challenged by the more racially strident NFL owners. Kenny Washington. Ray Bartlett, Jackie Robinson all played for the Pacific Coast Professional Football League. Strode and Kenny Washington were teammates on the Hollywood Bears from 1941-45. His chronically bad knees kept him out of the military.

Former USC baseball coach Rod Dedeaux once said Washington was more skilled than Robinson. According to an oft-repeated yarn, famed Brooklyn Dodgers manager Leo Durocher, attempted to sign Kenny Washington to the team before, Robinson. However he had a qualifying condition that Kenny Washington spend a year in Puerto Rico and pass himself off as a player from the island, but Washington refused.

At UCLA Kenny Washington and Woody Strode earned money as porters on Warner Brothers’ movie sets, and Kenny Washington picked up several film roles. In the meantime Strode was serving subpoenas and escorting prisoners for the L.A. County DA’s office, after Pearl Harbor Woody Strode joined an Army football team at March Field in Riverside, CA. When they could, Kenny Washington and Woody Strode played the Pacific Coast Football League (PCFL).

Kenny Washington earned all-league recognition in all of his four Pacific Coast seasons, despite several knee injuries, the most severe, in 1941, kept him out of the service. According to Legend, Kenny Washington stood in one end zone of Hollywood’s Gilmore Stadium, he then slung a football to the other endline. (“It was really 93 yards,” Washington would confess.) Washington spent the next year coaching the UCLA freshmen and finishing up his degree, then joined the LAPD.

Woody Strode grew within sight of the L.A. Coliseum, in what’s now known as South Central Los Angeles but was then called the East Side. As he entered Jefferson High, his father, a mason with Native American blood, moved the family to Central Avenue, the visible sign of the ‘Color Line’ indicating the border of the Black community. As a high school freshman, Woody was spindly at 130 pounds tautly stretched on a 6’1″ frame. By his junior year, Strode was strong enough for the Los Angeles Examiner to report, “He haunts his end like a departed spirit, taking out four men on one play if need be.”

By 1945, when he and Strode played for the Hollywood Bears, Washington found his former Bruins teammate with a touchdown pass that covered 62 yards, and he surpassed that with 65 and 67 yard bolts to another Black star snubbed by the NFL, Ezzrett (Sugarfoot) Anderson. “You’d have thought it was a revival for Black people,” Brad Pye Jr., the longtime sports editor of the Los Angeles Sentinel, says of those PCFL games. “People would come on Sundays after church, all dressed up. Thirty to forty percent in attendance were Black. Kenny was like a god. He did everything, and Sugarfoot Anderson could catch anything Kenny put up.”

Late in 1945 Hollywood Bears’ and the entire PCFL’s fate depended on the fledgling All-American Football Conference (AAFC) planting a flag in Los Angeles, with a team owned by actor Don Ameche, called the Dons. The “shoe” that had to drop, was a decision by NFL owners, seeking to hold in check the new league, granting Cleveland Rams owner, Dan Reeves, permission to move his Rams to L.A.

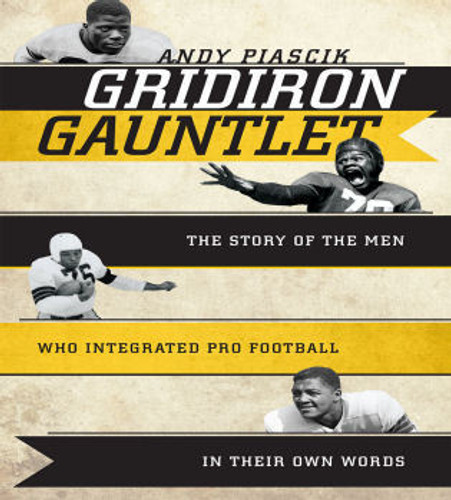

Andy Piascik says of the NFL in his book, Gridiron Gauntlet. “Their commitment to apartheid was seemingly stronger than their commitment to winning championships. The Bears under [George] Halas did not employ a single Black player in their first 32 seasons. The Giants began play in 1925 and did not sign any Blacks until 1948. The Steelers were all-White from the day Ray Kemp was released [in 1933] until 1952.” As for George Preston Marshall, owner of the Washington Redskins (page 64), Piascik writes: “He at least did not pretend there were no Blacks good enough to make his team. Unlike the others, he was honest enough to admit that he simply didn’t want them around.”

Kenny Washington was treated in a way that was a microcosm of so many Black players, his predecessors, contemporaries and those after him, for decades to follow.. Though he led the nation in total offense as a senior in 1939, and played 580 of the 600 minutes, in 10 games. He was also the keystone of the defensive secondary. Still, Kenny Washington was relegated to second-team All-America by Hearst, the AP, the UP, and Grantland Rice, while the East-West Shrine Game passed him over entirely.

This is even more of an outrage once you know that when Liberty magazine polled more than 1,600 collegians on the best player they had faced on the field. Kenny Washington was the only player that received a vote from everyone he played.

George Halas claimed to journalist Myron Cope in 1970 that “no great Black players were in the colleges then,” but despite the hardened prejudices of White selectors, no fewer than nine black players earned All-America honors, during the ‘Brownout’ and not one got an NFL tryout. Northwestern and, later, Chicago Rockets coach Dick Hanley who faced Iowa, when they featured Simmons 1934-36, called Ozzie Simmons, “the best I’ve ever seen.”

In 1937 Grantland Rice named Jerome (Brud) Holland of Cornell a first-team All-America end. A rising tide of Black talent was crashing onto the shores of college football: Julius Franks, a guard at Michigan; Bernie Jefferson, a running back at Northwestern; and Wilmeth Sidat-Singh, a quarterback at Syracuse. Simmons Iowa teammate, Homer Harris was team MVP as a junior.

As a senior, in 1937, he became the first Black player, ever, elected captain of a Big Ten football team. Historically Black colleges, all over the south and mid-Atlantic were bursting with talent that went unexamined. .

Regarding the obvious racial inequities in the voting, Pittsburgh Courier columnist Wendell Smith wrote, “When the All-American teams are selected this year, the one with Washington’s name missing can be called the ‘un-American’ team.” Washington did play in the College All-Star Game at Soldier Field, scoring a touchdown, and afterward, Halas asked him to stick around Chicago, saying he would “see what he could do,” Washington recalled. A week later the Bears owner told Washington that he couldn’t use him.

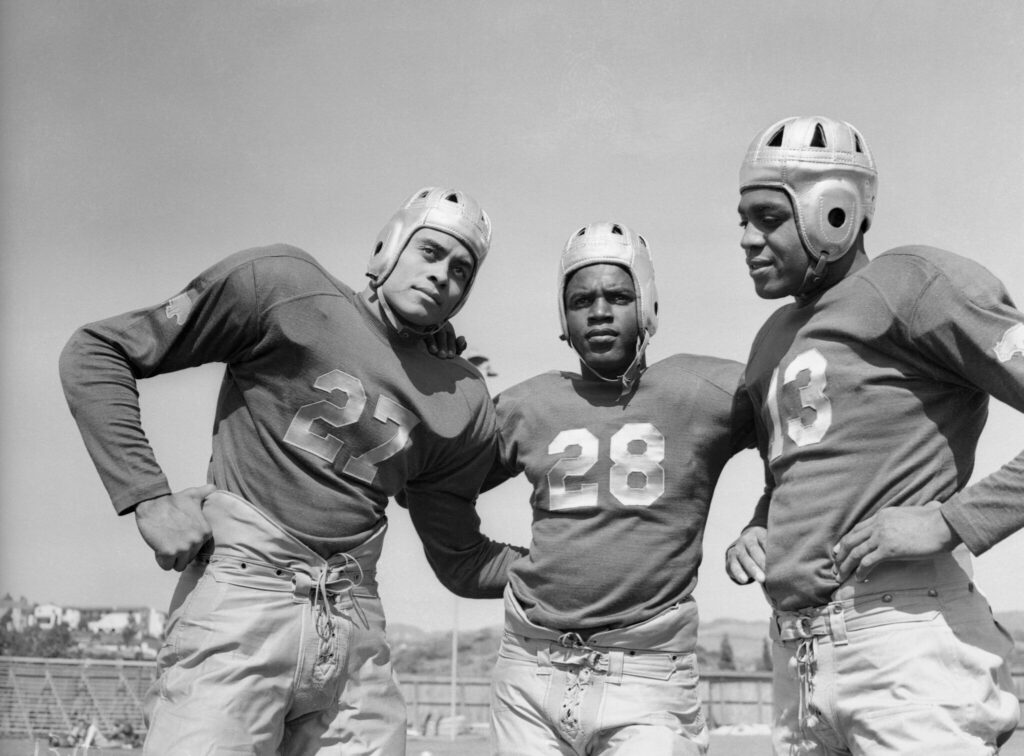

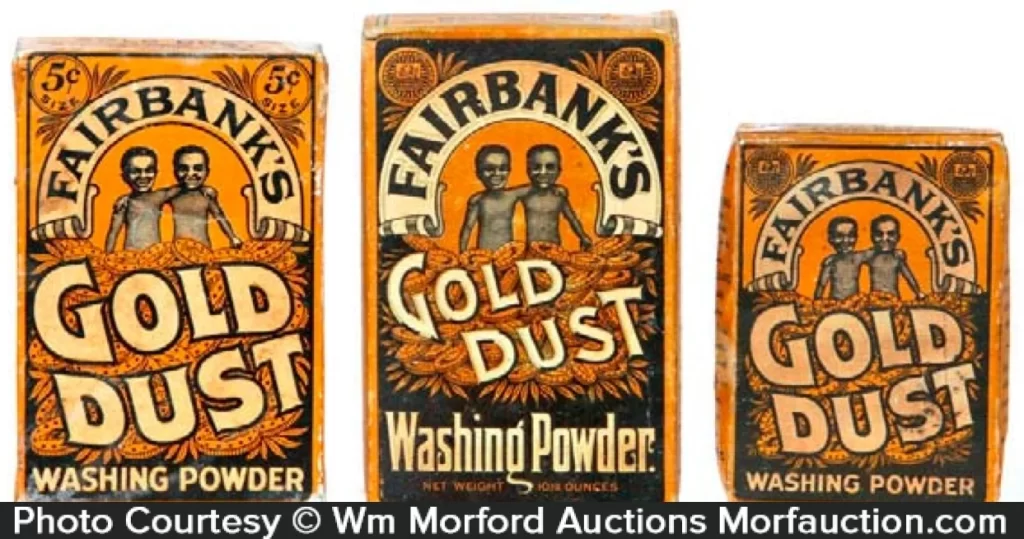

The two met in 1936, as freshmen at UCLA, which was developing a more welcoming attitude towards Black athletes. In the lingo of the age, a local sportswriter called them the Goal Dust Twins, a play on the two Black children featured on the box of Fairbank’s Gold Dust, a popular soap powder.

Kenny Washington’s nickname was “The Kingfish”, after a character in the radio comedy series Amos ‘n’ Andy—stood astride the Westwood campus. He played two seasons of varsity baseball, hitting .454 and .350, far better than Robinson. Rod Dedeaux, the longtime USC baseball coach, who scouted for the Dodgers, believed that Washington also had a better arm, more power, and more agility than Robinson.

When healthy, Kenny Washington was a rare athlete, even though he was both pigeon-toed and knock-kneed. Kenny Washington ran with power and a prodigious straight-arm. He stood nearly six feet-two inches tall and while he was 195 when he arrived, he was a strapping 212, by his senior year.

“He had a crazy gait, like he had two broken legs,” Tom Harmon, a teammate with the Rams, told SI before his death in 1990. “He’d be coming at you straight, and it would look like he was going sideways.” As a tailback in the single wing, Washington passed, as often and, as well as he ran.

In 1937, the Bruins were trailing USC 19-0, with five minutes to play and he threw a pair of touchdowns in 29 seconds, then added what could have been the winner if Strode had held on to his pass at the one-yard line. The first scoring pass traveled 62 yards in the air. UCLA coach Bill Spaulding went by the USC locker-room, post-game, to congratulate his counterpart, Howard Jones. “It’s all right to come out now,” Spaulding called through the door. “Kenny’s stopped passing!”

When Orin Ercel “Babe” Hollingbery the coach of Washington State harassed Kenny Washington with a vulgar cascade of racial invective, Washington went after him. Some opposing players would pile-drive Washington’s face into the lime lining the fields; while Strode and other Bruins remembered faces and meted out retribution. Strode remembered Kenny Washington was reluctant to play the same way: “If Kenny knocked a guy down, he’d pick him up after the play was over.”

This was the Kenny Washington, of whom former UCLA teammate Ray Bartlett once said, “He could smile when his lip was bleeding”. Things improved when, playing the wing-back position, Jackie Robinson occupied defenders while going in motion, emerging as a threat by Washington’s senior season. Robinson freed Kenny Washington, to lead the Bruins to an undefeated 6-0-4 season, including a scoreless tie with USC.

The game ended as UCLA’s final drive stalled inside the Trojans’ four-yard line. This pattern repeating in both dramatic games with USC seemed to prefigure a fate in which Washington would fall just short or lose out to the clock. When he left the Coliseum field as a Bruin for the final time, Washington received an ovation that sounded, as Strode put it, as if “the pope of Rome had come out.”

After Washington signed, the Tribune declared, “Halley Harding’s one-man crusade paid off in full.” Kenny Washington had already undergone five knee operations to remove cartilage and “growths”, prior to his NFL debut, at age 28. Now a running back in the T-Formation team, he could no longer freeze and tease defenses the ways that he did, as a Single-Wing tailback, who might run or pass. In Single-Wing the tailback or fullback takes the snap from the center. While the quarterback lines up behind the first tackle on the strong side.

He was most productive in the second of his three seasons, he finished fourth in the NFL in rushing yardage, led the league with 7.4 yards per carry, and ran 92 yards from scrimmage for a score shortly after being knocked unconscious by a Chicago Cardinals linebacker.

Motley and Willis didn’t integrate the NFL. They integrated the AAFC. Kenny Washington and Woody Strode integrated the NFL. The ‘Brownout’ ended only when the NFL ran afoul of Halley Harding. The other If lasting echo of the 1946 breakthrough, Branch Rickey college baseball rival, but football teammate of Charles Follis‘ with the Shelby Athletic Club, had noted Follis’s even temper in the face of taunts and cheap shots. Seeing Blacks and whites playing a violent collision sport, further emboldened Branch Rickey to call up Robinson to the Dodgers. Jack Roosevelt Robinson made his debut with the Dodgers the following season.

“Touchdown Tommy” Harmon, his old Rams teammate, confirmed this. “Woody was one of the greatest defensive ends I ever saw, but he never got a chance to prove it because of that fool coaching staff. In practice, you could never get near him. You never saw a man in better shape.”

Woody Strode was not long for the NFL. He learned of his release, in bed one morning, when several of Kenny Washington’s mob-connected friends from Lincoln Heights came by with the news. One of then, “the biggest bookie in Hollywood,” Strode said, had apparently heard Reeves and Snyder in a bar on Sunset Boulevard (“drunk on their asses,” in Strode’s telling) bragging about how they’d let Strode go. “[The bookie] said, ‘We don’t like the way they did it. We want to know if you want to fight it.’ I could have started a war.”

Strode went on to play two seasons in Canada and spent five years in Italy doing ‘Spaghetti Westerns’ and action films. On-screen he exuded an equipoise that one critic praised as “an effective counterpoint to the noise and confusion around him.” By the time he died of lung cancer in 1994, he had made more than 100 movies, including Sergeant Rutledge and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. His last film, The Quick and the Dead, was released in 1995, after his death.

Kenny Washington entered the NFL March 21, 1946, and fellow UCLA (and Hollywood) teammate Woody Strode signed May 7. Kenny Washington’s ruined knees meant his Rams’ career only lasted three years, but the impact he had and is still having is incalculable. Kenny Washington was inducted to the College Football Hall of Fame in 1956 and his number 13 jersey was the first to be retired at UCLA.

“Kenny was just a shell of himself when he played for the Rams,” says the Sentinel’s Pye. “If you could have seen him with the Hollywood Bears….” Still, Black Los Angelenos were appreciative of his body of work. When retired in 1948, the 80,000 fans who came out for a tribute did so to honor his entire career.

Pete Fierle, is a former chief of education programs for the Pro Football Hall of Fame in Canton, Ohio. He has spoken about the disparity between the telling of the stories of baseball and football’s integration. “My 11-year-old son could tell you Jackie Robinson’s name but not Kenny Washington’s or Marion Motley’s,” Fierle said.

That gracelessness wasn’t lost on the key players. “They didn’t take Kenny because of his ability,” Strode said. “They didn’t take me on my ability. It was shoved down their throats.” “Integrating the NFL was the low point of my life,” Strode said. “If I have to integrate heaven, I don’t want to go.”

The contrast between what was left of Kenny Washington as a Ram and his UCLA and PCFL days as a star could not be more stark. Jackie Robinson, in a 1971 article, he wrote in Gridiron magazine, called Kenny Washington “the greatest football player I have ever seen…. I’m sure he had a deep hurt over the fact that he never had become a national figure in professional sports. Many Blacks who were great athletes years ago grow old with this hurt.”

Kenny Washington, after football ended, worked as a distributor for a grocery chain and a whiskey distillery, a distinguished police officer for the Los Angeles Police Department, and served as a part-time scout for the Dodgers, in whose system his son, Kenny Jr., played several seasons.

In 1971, after Washington became ill with congestive-heart and lung problems, Strode hurried back from Italy to his old friend’s hospital room in the UCLA Medical Center. He wished to take Washington to Rome, to show him a place full of people like his Italian, Lincoln Heights, neighbors. Washington, was sadly, too weak to travel, he could bide his time scanning the UCLA Bruins’ football practice field, which he could see from his window.

Kenny Washington was just 52 when he died, another parallel with Robinson who died in 1972 at just 53. In his obituary in the Los Angeles Times, Waterfield said, “If he had come into the National Football League directly from UCLA, he would have been, in my opinion, the best the NFL had ever seen.”

“In what kind of peace is that supposed to leave a man?” Pastor L.L. White addressed the question in the eulogy of Kenny Washington, invoking St. Paul’s Epistle to the Philippians: “You live in a world of crooked and mean people. You must shine among them like stars lighting up the sky.”

Blue Washington died on September 15, 1970, at Mira Loma Hospital in Lancaster, California. He is laying in rest, at Evergreen Memorial Park, in Los Angeles. His son, Kenny Washington, was buried beside him in 1971. Kenny Washington is a recipient of a ”Court of Honor” plaque at the Coliseum. he was inducted to the College Football Hall of Fame in 1956. His number 13 jersey was the first to be retired at UCLA and he was inducted into the first class of the UCLA Athletic Hall of Fame in 1984 as a posthumous member.

NFL

NFL