By: Bill Carroll

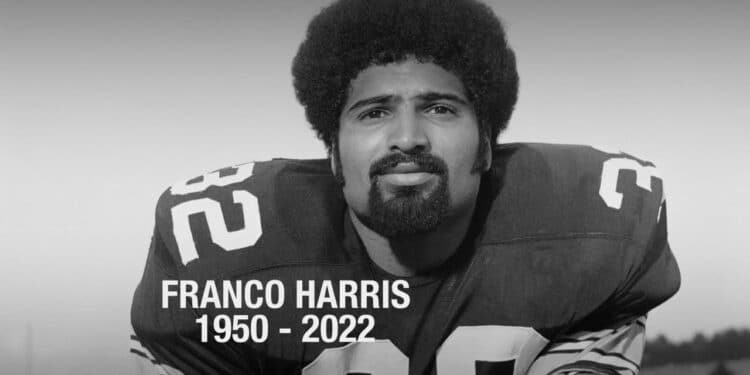

As we approach the 50th anniversary of the “Immaculate Reception” we are reminded of the saying that “man plans and God laughs.” That laughter is particularly pained as we are now saying fare thee well to 72-year-old Franco Harris.

Legendary Steeler Franco Harris Was Much More Than A Hall of Famer, his football accolades are well-known and oft-recited: despite being a fullback, largely used as a blocker for Lydell Mitchell, an All-American halfback at Penn State, Harris showed a blend of power, nimble footwork, speed and versatility that compelled Pittsburgh to select him with the 13th selection, in round one of the 1972 NFL Draft.

He was Offensive Rookie of the Year in 1972, after a stellar debut year, with 1,055 yards on 188 carries, a 5.6 yards per carry average. He also rushed for 10 touchdowns and caught four touchdown passes. He was widely considered the second or third best back of the era, only behind O.J Simpson and Walter Payton.

When he retired with 12,120 yards rushing, eight 1,000 yard seasons, a first team All-Pro, a pair of second team All-Pro selections, nine Pro Bowls and 1970s All-Decade, his place in football history was no longer in doubt. He also was an effective receiver out of the backfield with 307 receptions for 2,287 yards, a 7.4 yards per catch , and nine receiving touchdowns. Harris’s 12,120 career rushing yards rank him 12th all time in the NFL, he is 10th all time with 91 rushing touchdowns.

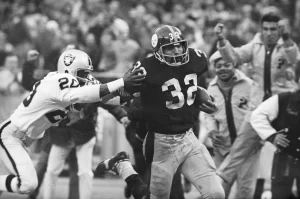

There are cardinal points in our lives, touchstones by which we can chart who we will become; September, 17, 1972 was one such point. It was a 1:00 PM EDT game from old Three Rivers Stadium. I had a football shaped birthday cake and I opened all of my presents prior to kick-off. That game on that day made me a Steelers fan.

The Steelers had not yet had the “greatest draft of all time” that would come in 1974 when they drafted: Lynn Swann, Jack Lambert, John Stallworth and Mike Webster, four hall-of-famers in five rounds. As a bonus they signed Donnie Shell as an un-drafted free agent. All five would later be inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

Future hall-of-fame head coaches, John Madden and Chuck Noll strode the sidelines. Both team’s owners Al Davis and Art Rooney as well as, Raider’s receivers’ coach, Tom Flores would find their way to Canton. As did Oakland’s starting receivers, Cliff Branch and Fred Biletnikoff, the Oakland Offensive line had three future enshrinees: Jim Otto, Art Shell and Gene Upshaw and future hall-of-fame quarterback Ken “The Snake” Stabler was George Blanda and Daryle Lamonica’s backup.

The underdog Steelers had finished 1971 with six wins and eight losses, Terry Bradshaw may have been another future Canton denizen, however his future was very much in doubt, he’d shown glimmers of greatness, but in the previous season his 13 starts had produced 13 touchdowns with 22 interceptions, 54.4% of his 373 attempts were complete and he rushed for five more scores.

The defense was already good and had stalwarts like Mel Blount, “Mean Joe” Greene, L. C Greenwood, Jack Ham, Andy Russell, Mike Wagner and Dwight White in place, but the young team had suffered three, one score losses in 1971. Success in 1972 would hinge upon improvement on offense and raising the level of talent across the roster.

In addition to Franco Harris the 1972 draft bought Pittsburgh a few key contributors, reserve offensive tackle Gordon Gravelle who came in the second, the third round pick was reserve tight end John McMakin, who is largely remembered in Steelers’ lore because during the “Immaculate Reception” McMakin’s block, from the flank of Raider linebacker Phil Villapiano, helped Harris score. Some Oakland fans still await a clipping call. Defensive tackle Steve Furness came in the in the fifth round, “Jefferson Street Joe” Gilliam, who for a brief time, would be the Steelers’ quarterback and was a Black pioneer at the position, was the 273rd overall selection in the 11th round.

This game proved to be a watershed moment in Steelers’ history and for Oakland it was a turning point as well, it was Al Davis’ maiden voyage as principal owner and general manager. 1971 had been a disappointment as it was the only season between 1966-77 in which the Raiders did not win the AFL/AFC West title. They finished 8-4-2 and their hated rivals, the Chiefs won the AFC West, soon to be eliminated on Christmas Day in a classic, 27-24 loss to the Miami Dolphins.

So in the first game of the regular season the brigands in Silver and Black were to quote Shakespeare, “in rotten armour, maarvellous ill-favoured” [ {sic} this was the Elizabethan-era spelling in the first Folio of Richard the Third.”] They likely assumed that they would assert their dominance over the upstart Steelers, however Pittsburgh carved out a 17-0 lead via a blocked punt that was cashed in, a Bradshaw 20-yard canter for a score and a field goal.

As expected the Raiders came storming back and George Blanda, who turned 45 that day, started their climb up with a 26-yard scoring strike to Raymond Chester, the Steelers responded with another field goal and Bradshaw’s two-yard plunge. It seemed that the Yellow and Black may overcome the Silver and Black.

However, Daryle Lamonica and Blanda combined to score 17 more as “The Mad Bomber” hit Mike Siani twice in the end-zone and Blanda handled place-kicking, as well as connecting on four of his 11 passes for 64 yards and a TD. Lamonica stood out with an eight of 10 mark as a passer, for 172 yards and two TDs, both to Mike Siani, including a 70-yard bomb. That was the past and future of the Raiders at QB, but the future stumbled. Ken Stabler hit on only five of 12 attempts for 54 yards and three interceptions.

Terry Bradshaw, the other future hall of fame signal-caller, accepted Stabler’s challenge and also threw three interceptions, but he contributed two TDs, rushing and was effective, if inefficient on 17 pass attempts. He was true on seven of those passes for 124 yards and an a 57-yard aerial score to Ron Shanklin. When the burgeoning Black and Gold held off the Raiders it signaled a new day.

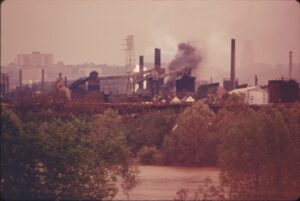

In 1972 Pittsburgh ended with a record of 11–3, winning their first-ever AFC Central Division title. It was the Steelers’ third-ever postseason appearance, their first in 10 seasons, and only the second playoff game since 1947. This came at a crucial time for Pittsburgh as a city.

Like many large US cities, built around the classic 19th century revolution’s industries like coal, steel and textiles, it was a time of change, the city’s population dropped to approximately 1 million, 838 thousand, down 4,000 from the year prior. Some of that was “white flight” as was found in so many urban areas nationwide. The steel and coal industries were still major employers, but trouble was brewing. By the 1970’s a growing economic, social and cultural void was being left in ‘Coal Country’ after the “smokestack” industries started shifting to natural gas.

For over 100 years company-built towns in southwestern Pennsylvania dotted the rail lines and rivers used to haul coal to steel mills and power plants. Major deposits, including the “Klondike” coal formation, a particularly productive part of the Pittsburgh Seam, was nicknamed that because it set off a frenzy similar to the Alaskan Gold Rush.

At the onset of the industrial revolution and even more post-Civil War, southwestern Pennsylvania became the epicenter of American demand for iron and steel, said Elaine DeFrank, oral historian for the Coal and Coke Heritage Center at Penn State Fayette.

Companies built coal “patches” or “camps” to serve needs for housing and resources for miners in the most rugged, isolated areas. ‘Tennessee Ernie’ Ford’s plaintive refrain “Saint Peter don’t you call me, ’cause I can’t go: I owe my soul to the company store.” May have been inspired by these mining camps. In the 1920s, nearly 50% of all Pennsylvania coal miners lived in company towns, according to a U.S. Coal Commission study.

“We had the coal that made the coke that made the iron and steel that built the buildings and bridges across America,” said Ms. DeFrank, who grew up in Amend, a Fayette County company town. She has, since 1992, been directing the Penn State coal museum, a collection of artifacts on the first floor of the campus library.

Up river from these mining towns was the city of Pittsburgh. Soon it was divided into ethnic enclaves that felt like, and in some cases previously had been, separate small towns, Chartiers borders Esplen to the north, Sheraden to the east and southeast, and Windgap from the south, west and northwest, Shadyside to the north, Point Breeze to the east, Squirrel Hill South to the south, Central Oakland to the southwest and North Oakland to the west.

Morningside, borders upon the Pittsburgh neighborhoods of: Highland Park to the east, East Liberty to the south, and Stanton Heights and Upper Lawrenceville to the west.Squirrel Hill, The Hill District, Bloomfield, also known as Pittsburgh’s “Little Italy”, Oakland, were filled with some established protestant families from Virginia and a mix of protestants and Catholics from Maryland, the French were also among the early settlers. The war of 1812 spurred industries that began to supplant trade as the primary businesses and soon steel came to the fore.

The Civil War drove coal and steel production into overdrive and after the war, steel framed buildings came in waves and The Home Insurance Building, completed in 1885 was the first ‘skyscraper’. Steel was in suspension bridges, tools, eating utensils, and finally automobile and airplane chassis, steel was a booming America’s skeleton during it’s adolescent growth spurt.

Western Pennsylvania has a huge population of Slovak-Americans, more than any other region in the country. To illustrate the importance of central Europeans in Pittsburgh, at the corner of Penn Avenue and Seventh Street in downtown Pittsburgh, there’s a blue and gold plaque that reads “The Pittsburgh Agreement.” This was a memorandum of understanding completed on 31 May 1918 between members of Czech and Slovak expatriate communities in the US. Formalizing that the two groups agreed to work together towards a united and independent state for Czechs and Slovaks. There was an aptly named “Polish Hill.”

In the past the Hazelwood neighborhood was composed of a largely: Hungarian, Italian, Slovak, Carpatho-Rusyn, Polish, and Irish population. With the construction of the Civic Arena in the Hill District large numbers of Black migrant populations made Hazelwood home. Also the Hazelwood Coke Works, Pittsburgh’s last operating steel mill, it closed in 1998, called Hazelwood home. Glen Hazel was the residue of federal housing projects for WWII defense workers.

World War II was a global tragedy but it was a boon to Pittsburgh and without it Franco Harris is never born. His father Cad Harris was born in Hinds County, Bolton Mississippi in 1920 and served in both WWII and Korea, rising to the rank of Sergeant first class. It was while stationed in Italy that he met and fell in love with Gina Parenti, later Gina Parenti Harris. She joined him at Fort Dix, in New Jersey after the end of the war, facing the challenges of learning English and raising mixed-race children in the late 1940s.

The Children: Albert, Franco, Alvara, Piero (Pete), Marisa, Luana, Giuseppe and Kelly Harris had active childhoods, Piero was also a Penn State standout, where he earned All American Honors in 1978. Like Franco he was a star at Rancocas Valley Regional high.

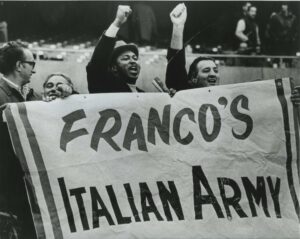

For Franco his lineage was a way to straddle two parallel and, at times, competing American stories, the one of the European immigrant who climbs via grit and determination and the grandchildren and great-grandchildren of chattel slavery, dealing with American apartheid and second-class citizenship. The Steelers had Black players who were popular, but none before had inspired the passion in multiple ethnic communities that Franco Harris did.

The formal version of Franco’s Italian Army was one-season phenomenon, mostly because the founders full-time business owners . Al Vento, of Vento’s Pizza, was friendly with members of the Pittsburgh Steelers who frequented his East Liberty shop. He and Tony Stagno, owner of Stagno’s Bakery (also in East Liberty), thought it would take an army to invigorate Steelers fans, who after 39 lackluster seasons needed motivation.

Vento remembered, “Franco Harris and I became acquainted through Sam Davis [Steelers offensive left tackle]. He was a customer of mine. And we all went down to the football games at Pitt Stadium. And then in 1970, when they transferred to the Northside, we went to the games [there]. We’d go every Sunday, and we went as a fun thing. So, when Franco joined the team, and we found out he was half Italian, we sort of was rooting for him at the game.”

With Franco’s blessing, Vento and Al Vento, Jr., Tony Stagno, Tony Stagno, Jr., Dom Stagno, Pat Stagno, Armand Zottola, Pat “Bronco” Signore, John Danzilli, Mike Capozzoli, Bob Capozzoli, and Joe Tamburrino founded Franco’s Italian Army. John Danzilli who was a service-member supplied helmets and drilled them. Vento and Tony Stagno provided food, some of which would somehow be smuggled into the booth of the legendary play by play man, Myron Cope, the father of the “Terrible Towel.”

Looking back, the football world is simultaneously much larger and much smaller fandom has become much more a choice at the buffet of entertainment rather than the generational auto-da-fé that it once was. In the social media saturated present there is no single way to explain the connection that a great running back, on a budding dynasty had with a city that was seeing its identity as the “Steel City” threatened by global trade and environmental concern.

The story of Pittsburgh cannot be told without telling the story of Franco Harris and the story of Franco Harris cannot be told without telling the story of Pittsburgh. One of many reasons that legendary Steeler Franco Harris was much more than a hall of famer was that he was imperfect, he was successful after he retired. He and Penn State backfield mate Lydell Mitchel created RSuper Foods which was a maker of nutritious food for schoolchildren.

He and Lydell Mitchell were part of the effort to save Parks Sausage Company. Among his missteps were very cozy relationships to casino operators and the most notable was defending Joe Paterno as the Sandusky scandal was reaching its crescendo. It is worth mentioning that even his flaws and mistakes were often rooted in love and loyalty.

He is not the first of my childhood football heroes to pass away and he most assuredly will not be the last, but this happening three days before the 50th anniversary of the “Immaculate Reception” and his number being retired, is particularly poignant and a bit unfair. I already miss him and his name transports me to a time of sugary breakfast cereals and watching “Schoolhouse Rock.” Like Franco those things are gone and no Christmas wish will bring any of them back.

Sources Cited:

The Coal and Coke Heritage Center of Penn State-Lafayette

Ciotola, N. P. (n.d.). Spignesi, Sinatra, and the Pittsburgh Steelers: Franco’s Italian Army as an Expression of Ethnic Identity, 1972-1977. (n.p.): (n.p.).

NFL

NFL