By: Bill Carroll

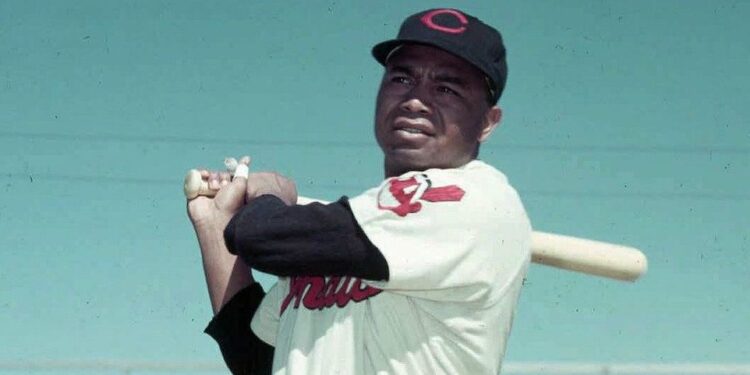

When Larry Doby, born in 1923, as Lawrence Eugene Doby in Camden, S.C., strode into the batter’s box, July 5, 1947, a mere three days after July 2, 1947, the day Effa Manley of the Negro National League’s Newark Eagles sold Larry Doby’s contract, to the Cleveland franchise of the American League. Once there he faced many of the same controversies, expectations, and pressures as did Jackie Roosevelt Robinson. Effa Manley called him and delivered the news “Larry,” she spoke, “you have been bought by the Cleveland Indians of the American League and you are to join the team in Chicago on Sunday.”

While pinch-hitting for Bryan Stephens, he struck out, but in his professional career, interrupted by WWII, stretched from 1942 to 1959, he had 1697 hits, with a .288 batting average, 273 home runs, 1,099, and a career OPS of .888. Those are very good numbers, quite similar to Fred Lynn or Tim Salmon, but those statistics barely scratch the surface of the man or the player.

“(Integration) was a part of history,” Larry Doby recounted years after. “If you’re not strong enough to deal with these things, then you don’t accept it.” In many ways his path to disrupting the Color Line was not only less celebrated than Jackie Roosevelt Robinson‘s, it was much more abrupt. After signing his contract with the Dodgers in October 1945, Jackie Roosevelt Robinson spent the entire 1946 season in the International League with the Montreal Royals, the Dodgers’ Triple-A affiliate. In the spring, Robinson was promoted to the Majors, six days before the start of the 1947 season, unofficially debuting in an exhibition game at Ebbets Field four days prior to the regular season.

For Larry Doby his ‘baptism by fire’ came a mere three days after he was signed. How tense was it? Bill Veeck hired two plainclothes police officers to accompany Larry Doby as he went to Comiskey Park. “I had to take it,” Doby said, “but I fought back by hitting the ball as far as I could. That was my answer” All of this despite the fact that Doby had been competing against White athletes much of his life. While he was quite young, his parents divorced and soon after, his father drowned in an accident. After the tragedy, Larry Doby lived in Camden with his grandmother, Augusta Moore and other relatives.

Larry Doby started playomg organized baseball at Boylan-Haven-Mather Academy, a private Black boarding school in Camden. Also, Richard DuBose, who had also coached Larry Doby’s father, and was a legendary presence in the Black baseball community of South Carolina, helped to mold the toungster.

Subsequently, Larry Doby was a multi-sport standout at Paterson’s Eastside High School. From 1938 to 1942, Larry Doby garnered 11 letters, as a multi-sport athlete in baseball, basketball, football, and track, at Paterson Eastside High School. His football team was invited to play in Florida one year after winning the state championship, but promoters would not allow Doby, who was the sole member of the team to play. In solidarity, his Eastside teammates voted to cancel the trip to Florida and decline the opportunity.

Shortly after that, Larry Doby joined an all Black semi-pro baseball team the Smart Sets during one summer vacation, reminiscent of his late father. Larry Doby’s late father, David, had played semi-pro baseball. Larry Doby was briefly, an unpaid substitute player for a legendary Black professional basketball team, The Harlem Renaissance. Larry Doby accepted a basketball scholarship to Long Island University (LIU) after completing high school.

However, during the Summer before Larry Doby officially enrolled in LIU, he took an offer to play with Negro National League baseball team the Newark Eagles, playing second base under the assumed name of Larry Walker, for the remainder of their 1942 season.

Larry Doby initially attended LIU because both he could play basketball for its future Basketball Hall of Fame coach Clair Bee and he could stay close to Paterson, NJ and his high school girlfriend, Helyn Curvy. Soon, two factors altered Doby’s plans to attend LIU, World War II and Negro League baseball. With the US joining the war, Larry Doby transferred from LIU to Virginia Union University, in Richmond, Virginia, because Virginia Union University had an excellent ROTC program.

Larry Doby had intended for his military service to be as an officer but, shortly after transferring to Virginia Union University, Larry Doby was drafted by the United States Navy. He served at the Great Lakes Naval Training School and various naval bases in the United States and the Pacific, while in the United States Navy from 1943 to 1946. After the war, Larry Doby decided to play baseball, instead of attending college. Before that, he was considering getting into coaching or teaching Physical Education.

“I never dreamed that far ahead. Growing up in a segregated society, you couldn’t have thought that that was the way it was gonna be. There was no bright spot as far as looking at baseball.”

But when Doby found that the Brooklyn Dodgers signed, future National Baseball Hall of Famer Jackie Roosevelt Robinson, to break major league baseball’s “color line”, everything changed.

“I felt I had a chance to play major league baseball. My main thing was to become a teacher and coach somewhere in New Jersey, but when I heard about Jackie, I decided to concentrate on baseball. I forgot about going back to college.”

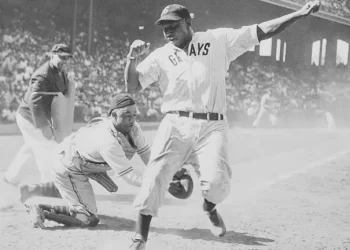

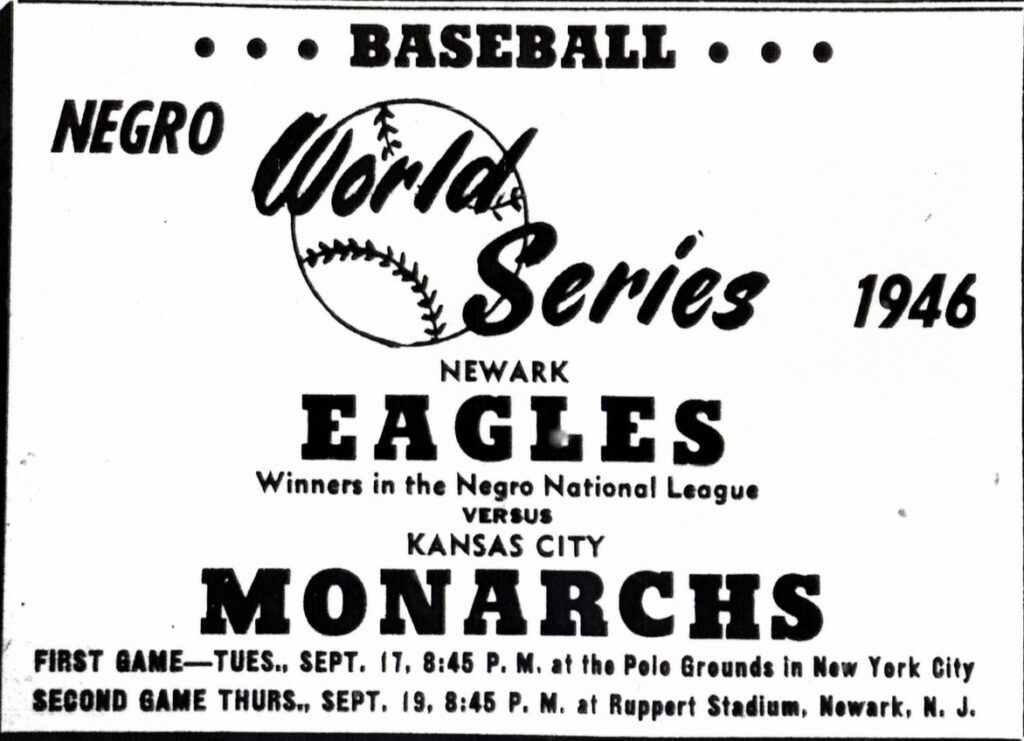

Returning to the states and the Newark Eagles, after his discharge from the Navy, Larry Doby resumed playing. In his prewar stint with the Eagles, Doby had a batting average of .309, with 14 runs batted in, in 81 at bats in 1942, a batting average of .301, with 22 runs batted in, in 103 at bats in 1943, and a batting average of .200 in five at bats in 1944. Returning in 1946, he was a vital member of an Eagles team that went 50-22-2 and took the Negro League World Series.

In his 233 at bats in 59 games that season, Larry Doby was a menace to pitchers he tallied: 85 hits, 12 doubles, an amazing 10 triples, 7 home-runs with 52 Runs Batted In, 6 steals and 29 walks. He hit for a .365 average, a .437 On Base %, slugged .592 for an OPS% of 1.030.

|

During his rookie season, things were difficult. When he entered the Cleveland clubhouse, many of Larry Doby’s team-mates gave him the cold shoulder, refusing to speak or even look at him. He played sparingly that season. Larry Doby, in a quiet and dignified manner dealt with pitchers throwing at his head. On the road with the team, he stayed in a separate hotel away from the rest of the team, and had to eat at restaurants in the Black community all while facing catcalls, jeers and threats from fans and players.

At first, Larry Doby was unspectacular for Cleveland, however he soon showed he was more than just a true major leaguer, he was headed for stardom. In 1948 he provided indisputable evidence that he was the real thing.

| 121 Games | 500 App | 439 AB | 83 Runs | 132 Hits | 23 2B | 9 3B | 14 HR | 66 RBI | 9 Stl | 9 CS | 54 BB | 77 K | .301 | .384 | .490 | .873 |

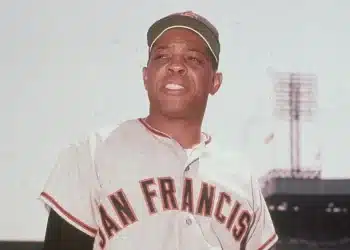

In 1949, Larry Doby batted .280 with 24 home runs and 85 RBI. That year, Larry Doby joined Robinson, Don Newcombe, and Roy Campanella as baseball’s first Black All-Stars.

Doby was an AL All-Star seven straight times beginning in 1949. In 1954, while pitch-hitting, Larry Doby became the first Black player in the American League to hit a home run in an All-Star game. In fact, The Sporting News, in 1950, named Larry Doby the best center fielder in baseball while Duke Snider and Joe DiMaggio were playing the position

In 1952 and 1954 Larry Doby swatted 32 home runs, leading the American League and in 1954 Larry Doby led the league with 126 RBI. At the end of his time with Cleveland, Larry Doby was traded to the Chicago White Sox for Jim Busby and Chico Carrasquel.

Larry Doby had a solid year for the Chicago batting .268 with 24 home runs and 102 RBI. In these twilight years, he was traded quite often. Larry Doby was sent to the Baltimore Orioles, but never played there. The White Sox traded him to Baltimore on December, 3, 1957, however the Orioles, like a 2nd baseman making the pivot, sent Larry Doby to the Cleveland Indians on April Fool’s Day of 1958. Larry Doby played his last season in the majors for the the Detroit Tigers and White Sox in 1959.

After the majors, Larry Doby spent in Japan for the Chunichi Dragons in 1962, for the proud man it was clear that his playing days were at an end. He moved into coaching for the White Sox, Cleveland, and Montreal Expos. He was even in the running to be a historical first. He was rumored to be in the running to become the majors’ first Black manager. However another Black Hall of Famer, Frank Robinson was named on April 8, 1975, to the post of player/manager with Cleveland.

When the Chicago White Sox fired Bob Lemon in 1978, Doby got the call, but the White Sox went only 37-50 under his direction, so despite the fact that the team was improving. Larry Doby was not retained by Bill Veeck and left his beloved game to work for the NBA‘s New Jersey Nets as director of community relations, eventually returning to baseball in 1990, as an employee of Major League Baseball Properties, handling the licensing of former players and a special assistant to American League President Gene Budig, until his final retirement in 2003.

In 1994, Cleveland Indians retired Doby’s number 14 on the 50th anniversary of his debut and the first year the team played in, what is now, Progressive Field. Most recently, on the 76th anniversary of Doby breaking the color barrier in the American League, manager Terry Francona wrote the Hall of Famer’s 14 on his cap before last Wednesday’s game.

As the national anthem was being played, Francona said he looked at Larry Doby Jr., who was in attendance and standing nearby with other family members, and felt moved to make his own personal tribute.

“His dad couldn’t eat at the same place my dad could, and I marched in and grabbed a pen,” Francona said prior to Thursday’s matchup. “Not that that’s the biggest statement in the world, but I grabbed a silver pen and put a 14.”

In 2015 Cleveland unveiled a statue of Larry Doby at the entrance of the ballpark. For the 75th anniversary of his debut, the team wore patches on their uniforms. Last Wednesday night, the Guardians gave away commemorative Doby caps along with playing a video tribute to him on the stadium’s giant scoreboard.

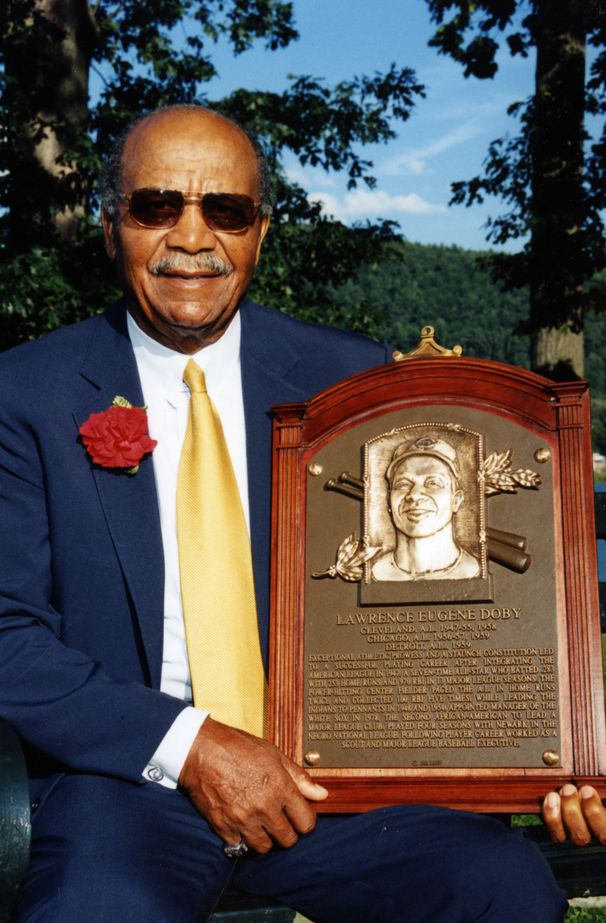

On July 26, 1998, the Veterans Committee voted Larry Doby into the Hall of Fame. Though the road had been hard and the wait was long, as was his way, he handled it all with class and distinction, even though he had his left kidney when a cancerous tumor was detected, he attended and was pleased.

“This is just a tremendous feeling. It’s kind of like a bale of cotton has been on your shoulders, and now it’s off.”

Larry Doby died of bone cancer, on December, 18, 2003, at the age of 79. In his career he seemed to often be second in so many of baseball history’s turning points, regarding racial progress. For that reason he is somewhat overlooked but I strongly believe that the American League should have July 5 as Larry Doby day and a 14 flag should fly in every ballpark, that is the very least that this hero deserves.

NFL

NFL