By: Zachary Draves

In the fall of 1992, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill was in the national spotlight. Against the backdrop of the uprising in Los Angeles that summer after the acquittal of four white police officers in the beating of Rodney King, students organized on a variety of issues pertaining to race, including the construction of freestanding black cultural center on campus.

The Sonja Haynes Stone Center for Black Culture and History was named after Dr. Sonja Haynes Stone who was a well renowned scholar of African American Studies at UNC. The Center was established to celebrate African American history and culture. The construction of the center was first approved in 1988 but it was originally located inside the 900 square foot Frank Porter Graham Student Union. However, the capacity for the center began to grow and as a result a movement of students, faculty, and community members began for a freestanding center.

Furthermore, they put out additional demands which included increased wages for UNC’s housekeepers and an endowed professorship in Dr. Stone’s name. These were brought to the attention of Chancellor Paul Hardin, who failed to meet any of demands, even though he supported the construction of the center but within the bounds of the student union. He even went as far as accusing a free standing center of promoting segreation.

Then university trustee John Pope lit a fire when he said “it seems to me if (black students) are interested in a Black Cultural Center, maybe those students should attend a black university.”

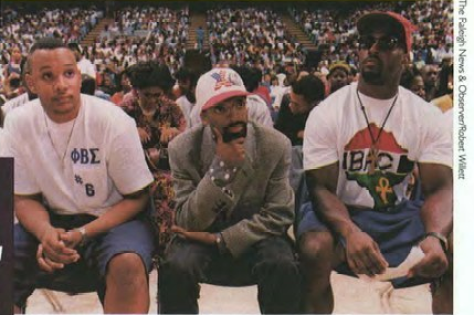

All it took was logistical errors, empty promises, and open bigotry to intensify the movement to where students showed up in numbers reminiscent of that of the Vietnam War era. It was also a multicultural effort as Asian, Indian, and Hispanic student groups expressed public support for the project. But what thrust this into the national consciousness was when four UNC football players John Bradley, Jimmy Hancock, Malcolm Marshall, and Timothy Smith established the Black Awareness Council which gave black athletes a voice on campus and they became a regular presence in the movement.

(Courtesy: Kelly Greene/Black Ink)

On September 3, a protest was held outside the home of Hardin in which the players attended. Then on September 10, they organized a peaceful demonstration outside his office and presented him with a letter outlining their demands which included choosing a location for the center by November 13. Soon afterward, a BAC rally was held in the student social center.

(Courtesy: Carolina Alumni Review)

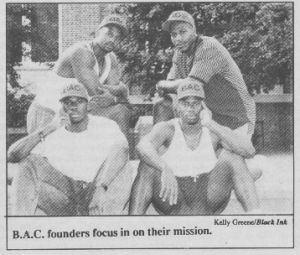

The visibility of student athletes lending their unconditional support for social justice was uncanny at the time considering that the sports world was largely in throws of the Michael Jordan ethos of “republicans buy sneakers too.” This was so unprecedented that it soon got the attention of famed filmmaker and rabid sports fan Spike Lee, who was in the middle of promoting his now classic film Malcolm X, which told the story of the famed activist played by Denzel Washington.

Lee, who just happened to be a distant cousin of Dr. Stone, attended a large rally in the Dean Smith Center in which 7,000 students were present. In his ten minute speech, he said that he was most impressed by “the fact that this movement is led by athletes”.

(Courtesy: DTH/Debbie Stengel)

The movement would eventually be covered in the New York Times by famed sports writer William Rhoden and receive the support of the Rev. Jesse Jackson and Dr. Khalid Abdul Muhammad of the Nation of Islam.

Eventually, a 13 person committee was formed to decide the future of the Sonja Haynes Center. Among those were Dolores Jordan, Michael Jordan’s mother and Harvey Gantt, the first black mayor of Charlotte, North Carolina. No student leaders were part of the committee which rendered much skepticism in the movement on whether they were in fact serious about their demands.

On October 5, the committee 10-2 for a free standing black cultural center. Paul Hardin wasn’t on board at first but vaguely came around on October 15 when he said he supports a “free-standing facility to house the center”. At first, student activists were confused and angered and the statement had to be clarified. The students would eventually have a seat at the table on the construction of the center and demanded that the already established advisory committee would have a say and that it would be mostly student run.

The freestanding Sonja Haynes Centerfor Black Culture and History broke ground in April 2001 and would be opened in August 2004.

30 years later, NBS was able to get in touch with former UNC football player and BAC co-founder John Bradley. In an email interview, he discusses the movement, the involvement of him and his teammates, his feelings on athletes and social justice, and the legacy of the Sonja Haynes Center.

But he begins with where he is now.

(Courtesy: John Bradley)

ZD: What do you do these days? What was your major? Career, family, etc.?

JB:I graduated with a degree in African America Studies at UNC and received my MBA from Charleston Southern University. Father of two children one at UNCW and one in the 7th grade. Long career in corporate/retail sales management in the technology industry. Currently, I am an entrepreneur who helps busy people maximize their physical, mental, and business health through customized coaching/mentoring.

ZD: 30 years ago, what was what it about the construction of the Sonja Haynes Center that made you and your teammates ultimately decide to lend your public support?

JB: There were a few reasons to get involved. First, there wasn’t any involvement by athletes. This is a time before social media so athletes were the influencers and we knew that we could add that fuel to the movement. We all had utilized the BCC (office) and it had been a great resource for learning and community and truly believed a full center would add so much more to our experience. We were all very fond of Dr. Sonja H.

ZD: Did you expect that it would get national attention?

JB: Yes we absolutely expected our involvement to get local, state and national support which is one of the positives that we could add to the movement. There was no Google or smartphones back then so we relied on motivating the media and campus to spread the word of the struggle for the Sonja Haynes Stone Center.

ZD: Spike Lee famously came to campus after hearing about your guy’s involvement. What did he say to you guys? What was it like to have somebody like that involved in the cause?

JB: Spike Lee was very helpful in amplifying the issue of the BCC. He was getting ready to release his movie on Malcolm X, played by Denzel Washington, so it fit with the struggle that the black community generally deals with in pushing for change. He was very encouraging and sought to amplify is versus taking the spotlight which meant a lot. It was great having him and leaders like Jesse Jackson, Dr. Mohammad and various local leaders show up to support us.

ZD: Do you keep in touch with your teammates and Spike?

JB: No I don’t and don’t think any of the others do either.

ZD: Was it ever difficult bringing this up to your coach?

JB: No it wasn’t difficult. We were leaders on campus which coach Mack Brown and others encouraged. Their main concern was to represent ourselves and family well and to make sure we kept ourselves safe because speaking out often places a target on your back.

ZD: How much did the spring and summer of 1992 with the Rodney King beating and the LA rebellion influence you and your teammate’s decision to get involved?

JB: The Rodney King beating & LA rebellion was surely a catalyst for being involved in campus activism. This was one of the first examples in my lifetime of visually seeing a horrible act captured and broadcast with no consequences. It reinforced that the BCC was not going to be built by just quietly asking for its construction.

ZD: What goes through your mind when you see athletes speaking out today on social justice?

JB: It makes me happy to see athletes standing up and speaking out today. From little league to the pros it’s not foreign to see or hear an athlete take a stance on an issue. Athletes are looked up to and admired and often have a louder voice just because of the status that they have. I know it can be difficult because it’s not a job that you are looking for as an athlete, but I believe it’s a responsibility that has to be utilized.

ZD: When you look at the Sonja Haynes Stone Center today and reflect on the movement that led to its construction, how would you want history to remember all that?

JB: That the Sonja Haynes Stone Cultural Center is a facility that was built from struggle. That the center was supported by a diverse group of people who believed that UNC Chapel Hill could continue to be a leader in social justice and education. That it’s the responsibility of the students, faculty and administrators to continue to invest, support and participate in building the programming and access to the student body, local community and state.

NFL

NFL