By: Jeffrey Newholm

In sports as well as life, accomplishments are often seen as a matter of pride. But some very talented athletes embrace their egos to such an extent that they become locker room poison. On the other hand, many very talented men are extremely prideful. The film Jobs demonstrates that Steve Jobs was a very mean and demanding boss, yet still a very successful one. But what is the proper balance in life between embracing the ego and fighting to tame it? I’ve pulled some thoughts from popular philosophers to take a look at the arguments for pride. Keep in mind there’s no “right” answer to questions like these. Great thinkers have been arguing incessantly about these issues for centuries, and disagreement is certainly no sin.

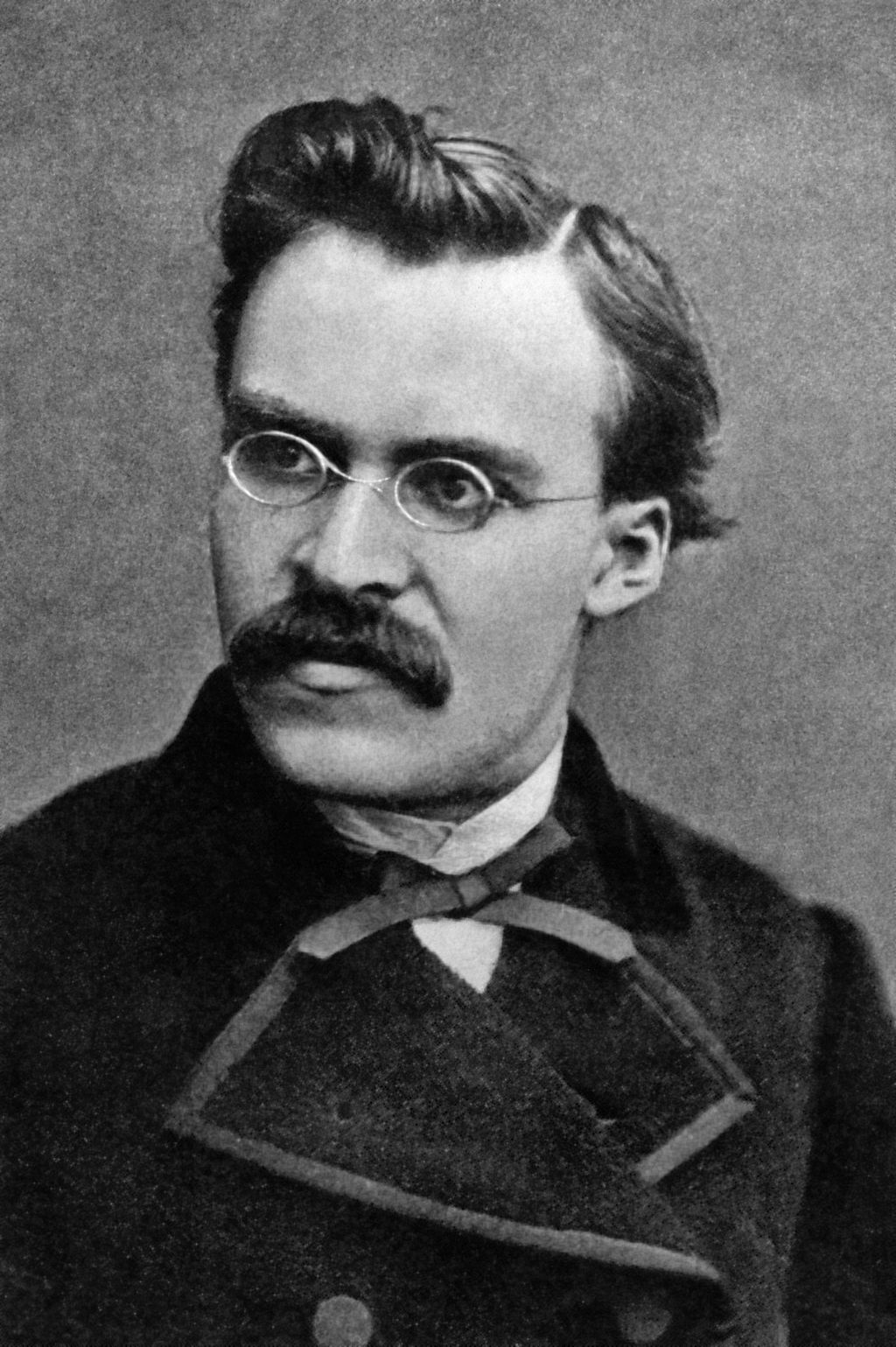

The best thinker to analyze egoism was iconoclast philosopher Freidrich Nietzsche. Nietzsche is famous for belittling sacrosanct ideas and boldly making outrageous statements. The editor of the 1993 Prometheus Books translation of his magnum opus Thus Spake Zarathustra warned that “although some of Nietzsche’s outrageous statements have been misunderstood and abused by political and ideological movements, his thought cannot be ignored” (p. 25). I think this is a fair point. Nietzsche writes at a brilliant level of prose, a level so brilliant that multiple readings of the book are needed to get even a basic understanding of his ideas. Unfortunately, it’s easy to see how those with weak character have misused his ideas.

One of Nietzsche’s central ideas is that some men are so great they transcend the boundaries of good and evil and can create their own standards of right and wrong. Zarathustra states that, “This somnolence did I disturb when I taught that no one yet knows what is good or bad:-unless it be the creating one!” (p 216). There’s definitely a positive spin to be put on this line of thinking. I’d easily agree with Nietzsche that “Hateful to it altogether, and nauseating, is he who will never defend himself, he who swallows down poisonous spittle and bad looks, the all-too-patient one, the all-endurer, the the all-satisfied one: for that is the mode of slaves” (p. 210). Examples of bad fruits of egoism, sadly, are all too common.

A notable instance of out-of-control egoism is the famous legal case of Leopold and Loeb. In this case, two privileged youths had it through their heads that they were Nietzschean “Supermen”. They thought they were justified in taking an innocent man’s life because they could make their own standards of good. In a similar vein, Enron CEO Jeffrey Skilling, after reading evolutionary bestseller The Selfish Gene, thought he was hard-wired to be self-interested and went on to steal millions. The problem with Nietzsche’s idea of transcending good and evil is that everyone wants to be the master in a master-slave hierarchy. No one in his right mind thinks of himself as a slave. Right and wrong is a matter of continual self-discovery; no one can just make up the rules himself. Nietzsche is a great thinker, but many of his ideas are truthfully outrageous.

A more contemporary thinker on egoism is bestselling 20th century novelist Ayn Rand. Rand taught that selfishness was a virtue, not a vice. She believed the ego was the fount of all of man’s productiveness, and argued the ideal society consisted of each person working solely for his own benefit. For this analysis I used contemporary Objectivist David Kelly’s monograph Unrugged Individualism: The Selfish Basis Of Benevolence. Kelly tries to interpret Rand’s thoughts in a more nuanced way, looking at how benevolence and good will plays a role in enlightened self interest.

In a familiar fashion, Kelly argues from the beginning that “the critics who accuse Rand of advocating the greedy pursuit of one’s own gain at the expense of others are grossly misrepresenting her views”. Yet it’s concerning that most of the justifications Kelly gives for benevolence are roundabout justifications for selfishness. He states that “The function of benevolence in the pursuit of our rational self-interest, then is to create opportunity for trade by treating other people as potential trading partners. The value at which it aims is trade-and the vast expansion of wealth, knowledge, and self-affirmation that trade makes possible”. At the conclusion of his discussion on benevolence, he summarizes his thoughts by arguing that “On the Objectivist view, by contrast, helping others is a self-interested action, and the choice of how much to help is an economic decision like any other.”

Why is helping others justified primarily by self interest? Kelly makes a clever and well thought argument that traces back to The Fountainhead. Objectivists see the world through a “benevolent universe” prism. They see life as primarily about achievement and success. Altruists, conversely, wants to see other people suffer in order to have opportunities to be moral. I would disagree with this premise on the grounds that altruism isn’t about wanting to see other people suffer. It’s about offering what comfort one can in a world where suffering is ubiquitous. I’d side more with famously glum philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer who had a pessimistic view of human existence. He argued that human life is primarily about suffering and our struggle to find meaning in its overbearing presence.

To give just one sample of his thoughts: “Unless suffering is the direct and immediate object of life, our existence must entirely fail of its aim. It is absurd to look upon the enormous amount of pain that abounds everywhere in the world, originating in needs and necessities inseparable from life itself, originating in needs and necessities insperable from life itself, as serving no purpose, as being the result of mere chance”. We don’t have to want to see people suffer to be altruistic. Opportunities to help those in need have always and will always be present.

Kelly at one point quickly mentions an idea that more properly characterizes altruism. He says that “one’s own life is improved by living in a world with better, happier, more fully realized people in it”. By that line of reasoning altruism doesn’t even require someone else’s suffering. It instead requires efforts to improve another’s life, even if that person is doing well. This attitude is warmer and more fulfilling than viewing people as objects to be manipulate.

It’s understandable that top tier athletes can be egoistic. But I think the ones most fondly remembered are those who eventually managed to find humility. It’s telling to compare athletes who are egotistical with those who manage to stay humble in spite of their success. The NBA is full of egomaniac stars like James Harden and Carmelo Anthony who can’t achieve team success. Both the Knicks and Rockets have collapsed after a brief time of contention. I think an amazing and inspiring example of humility is Lou Gehrig’s farewell address.

Gherig somehow had the courage to make the following statement: “Fans, for the past two weeks you have been reading about the bad break I got. Yet today I consider myself the luckiest man on the face of this earth.” Many would prefer to be Nietzsche’s standard-setting master or Rand’s proud producer. But I think those characters wouldn’t be able to handle suffering with the fortitude that Gherig did. It’s natural to be proud after achieving success, and successful men have a lot to be proud of. But as Leopold, Loeb, and Skilling found out, unchecked ego can lead to disaster. Humility, not egoism, is what leads to true magnanimity. Only one can be the greatest man in the world, but eventually anyone can feel like the luckiest.

You can follow me on Twitter @JeffreyNewholm and our blog @NutsAndBoltsSP.

NFL

NFL