By: Zachary Draves

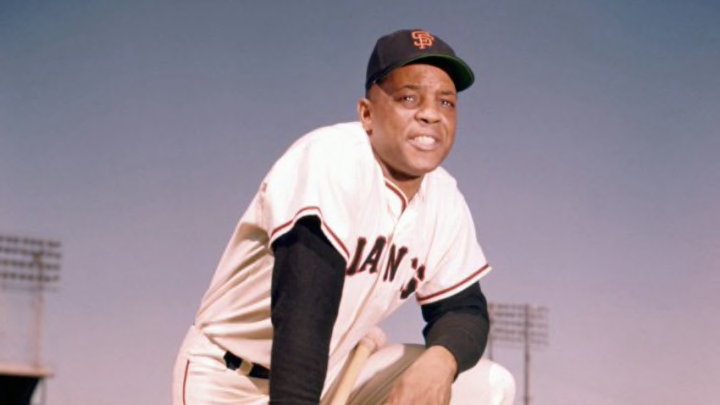

Willie Mays was the essence of a five-tool player who could do everything that was required of a baseball player. He could hit for average, power, field, throw, and run.

If anything, he set the model for such a player.

He possessed an abundance of charm and cool that endeared him to the masses, particularly at a time when it was a rarity for black athletes and other cultural figures to have such crossover appeal.

If anything, he was the godfather of crossover appeal.

His longevity beginning with the Birmingham Black Barons of the Negro Leagues in 1948 lasted through his 23 seasons in the Major Leagues with the New York/San Francisco Giants (1951-1972) and then with the New York Mets (1972-1973). All the while maintaining the same 32-inch waist.

If anything, he exemplified the prioritization of mind, body, and spirit.

He was Willie Mays, the Say Hey Kid, perhaps the greatest player ever.

(Courtesy: Kidwiler Collection/Getty Images)

His passing on Wednesday at the age of 93 brought on a tremendous display of love from those young and old who understood what he represented.

He exuded the definition of playing for pure love of the game. All he wanted to do was to play at his absolute best and have a good time doing so. In turn, the fans reciprocated and basked in the enthusiasm of watching him play or if they had the good fortune of being in his presence.

They all carved a special place in their heart for Willie and passed it onto the generations that came after, thus unleashing a multi general outpouring of affection.

In defining what it means to be a five tool player, the numbers say it all. He hit 660 home runs, 3,293 hits, won 12 Gold Glove Awards, a lifetime batting average of .302, 339 stolen bases, and 23 All Star game appearances.

Of course he is seared into the collective imagination with arguably the greatest outfield play in history with the iconic basket catch in Game 1 of the 1954 World Series at New York’s famed Polo Grounds, resulting in the Giants upsetting the then heavily favored Cleveland Indians in a four game sweep and Willie’s only World Series title.

(Courtesy: Youtube)

But that moment was not an anomaly.

“He leaped up at 40 years old, jumped over Bobby Bonds, crashed into the fence and kept the ball in his glove,” said Nelson George, writer and director of the 2022 HBO documentary Say Hey, Willie Mays!

George also told Team NBS Media in a phone interview about another catch Willie made while playing against the Brooklyn Dodgers.

“He caught the ball and crashed into the fence at Ebbets Field,” he said. “Willie said that was his best catch.

He would make an art out of routine catches out in centerfield, the way he swung the bat, and being aggressive on the base paths with everyone clinging with anticipation of what miraculous move was in store.

In other words, he was the radiation of excitement that was emblematic of a rich tradition of black athleticism.

The line can be drawn from Jack Johnson to Sugar Ray Robinson to Willie.

That line then stretches to Julius “Dr. J” Erving to Magic Johnson to Michael Jordan to Ozzie Smith to Deion Sanders to the Michigan Fab Five to Kobe Bryant to LeBron James and others.

Black athletes with style and flare while also expressing black joy and passion that had been long repressed by American racism.

He also paved the way for those names to become everyday staples in mainstream American popular culture with his groundbreaking appearances on television programs such as The Donna Reed Show, Bewitched, and What’s My Line.

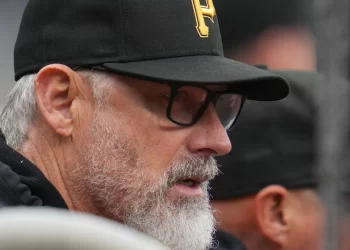

(Courtesy: Kidwiler Collection/Diamond Images)

At the time, he was not outspoken on civil rights, but in many aspects he didn’t have to because his game was his megaphone and his marketability was his seat at the table.

Willie was marketable, but he wasn’t marketable because he was black, said Dr. Louis Moore, Professor of History at Grand Valley State University in a phone interview with Team NBS Media. “Willie was always just comfortable being Willie.”

It was also his trajectory from New York to California and then back to New York that captured a time of rapid growth and change in America during the post World War II era even while the country was struggling to come to terms with race.

“Willie represents a change in America,” said Dr. Moore. “He’s moving from New York to California. This is a new America. He makes a lot of people comfortable at a time of change. “

But what also makes Willie’s legacy more indelible was that he played in an era where baseball was truly the national pastime and in particular New York was the center of the baseball universe with the Yankees, Giants, and Dodgers.

Willie was pitted against fellow center fielders Mickey Mantle and Duke Snyder in the never ending debates amongst fans over who was better than sometimes go personal.

There was an aura around the game that doesn’t exist any more as baseball has largely faded from the national sporting landscape at least compared to where it was in Willie’s day. Baseball has been relegated to a more regional status and there is an absence of present day baseball heroes that come close to Willie.

“The outpouring you see reflects that he was a legend at a time when baseball mattered, ” said Dr. Moore. “Few athletes can capture that attention and imagination.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23975858/1405650999.jpg)

(Courtesy: Walter Leporati/Getty Images)

When it comes to his contributions to black and eventually Latino players, he was the guy to go.

“The black players came to Willie’s house, said George. “His place became a sanctuary. Any player of that era had a similar story. All those players that came through the 50s and 60s he knew all the players. He wasn’t just a leader of the Giants, he was a leader of that generation of Black and Latino players.”

Everyone had a story about Willie and how he touched their lives and how his unique sense of humor left them cracking up with George providing one through Willie’s son Michael.

“Bob Gibson is the most fiercest pitcher of the 1960s, ” he said. “They are home during Christmas and Bob Gibson comes to visit and Michael says “Bob Gibson is here” and Willie says “don’t let that man in he will kill me”.

(Courtesy: Nuccio DiNuzzo/Getty Images)

Although his body eventually gave way by life, there was something that George took away from making the documentary and spending such precious time with Willie in what ultimately were in his final two years.

“Yes your body betrays you in a lot of different ways as you get old, but your spirit and your sense of humor don’t go away and in fact are sharpened.”

Willie Mays was simply a man who loved what did and wanted everyone to join him.

To the Say Hey Kid, thank you for the ride.

NFL

NFL