By: Zachary Draves

2023 was a renaissance year for black women.

Certainly Beyonce dominated the pop culture zeitgeist with her aptly named Renaissance Tour that grossed $579 million and its subsequent documentary film added $42.5 million in total global box office numbers. But as it turned out, there was still plenty of glitter to go around, especially in sports.

This year saw a splurge of black female athletic excellence across multiple sports with respective journeys that each possessed a trifecta of distinct flare, style, and joy, much like the Renaissance Tour.

Despite her “you can’t see me” gesture, Angel Reese was seen with her unapologetic competitiveness as she carried the LSU Tigers to their first-ever national championship. Simone Biles came back to prominence and once again dominated the gymnastics world as she prepares to conquer the world again in Paris next year. Sha’Carri Richardson also came back into the fold and solidified her status as the fastest woman in the world. Coco Gauff won hearts everywhere by winning the US Open in grand style. A’ja Wilson entered the prime of her career utilizing her trademark fierceness as she and the Las Vegas Aces won their second consecutive WNBA title.

When all is said and done, this year will be looked at as a year where black women defined sports. But what might not be acknowledged, until now, is that there was a particular historical foundation for all this success that broke ground 35 years ago.

It came in the form of one of the most vivacious athletes to ever blossom who went by “Flo Jo”, but whose full name was Florence Griffith Joyner.

(Courtesy: Mike Powell/Allsports/Getty Images)

In 1988, Flo Jo captured the attention of the world at the Seoul Olympics with her dazzling athleticism and equally dazzling fashion sense as she won three gold medals in the 100 meters, 200 meters, and the 4×100 relay. She also managed to capture a silver in the 4×400 meter relay.

All the while she wowed everyone with her originality as a true fashionista. She came with her free-flowing hair, brightly colored running outfits that sometimes were one-legged, and long multicolored fingernails that were unmistakable.

![]()

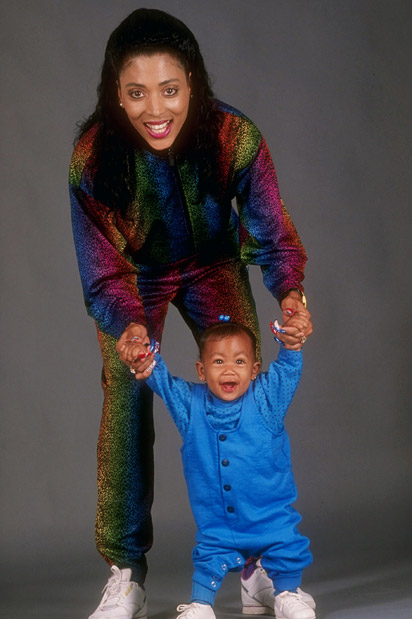

(Courtesy: People.com)

All of which was her own.

Flo-Jo set a precedent for women in sports, especially black women, that it is possible to exude strength and style, to display beauty and boldness, to be feminine and formidable, and to not have any of that contradict each other.

In other words, to have agency both athletically and aesthetically.

(Courtesy: Ron Galella LTD./Ron Galella Collection Via Getty Images)

“She was just a role model for black feminism and challenging stereotypes, particularly about black women in sports,” said Dr. Letisha Brown, Assistant Professor of Sociology and an affiliate of the Women’s, Gender, and Sexualities Studies program at the University of Cincinnati.

In the midst of such greatness, Flo-Jo was besieged by critics who alleged that she was using performance-enhancing drugs and that her wins weren’t legitimate. As a result, she was subjected to the aggressive over policing of her body that black women in sports and society have been subjected to for centuries with the notion that black female bodies don’t warrant protection nor embody the aspects of what is deemed feminine, attractive, and even athletic.

She denied the allegations and what’s even more profound is that she stood firm in her truth and never relinquished her integrity.

In her later years, Flo-Jo would become a true, shall we say, renaissance woman. She was an actor, author, and fashion designer, most notable for designing the uniforms for the Indiana Pacers in the early 1990s.

Her fashion was integral to her identity and allowed black women to be their authentic selves.

“She embraced her kind of fashion icon status off the track as well as on the track showed fashion as a form of resistance for black women athletes” said Dr. Brown. “You might be intimidated by this body and this culture might be hypermasculine, but you can’t deny this softness and femininity to it as well.”

She was also married to Olympic triple jumper Al Joyner, sister-in-law to Jackie Joyner Kersee, and mother to her only child Mary Ruth.

(Courtesy: Kevin Winter/Time Life Pictures/Getty Images)

(Courtesy: Tony Duffy/Getty Images)

Tragically on September 21, 1998, she unexpectedly passed away at the age of 38 due to an epileptic seizure while in her sleep. Some rushed to claim that PEDs had something to do with her untimely death, but her autopsy said otherwise.

Yet the urge to overly scrutinize and marginalize a black woman posthumously reeks of pure misogynoir, the racialized sexism towards black women and girls. However, it is not surprising when looking at the historical and present-day treatment of black women and girls, including in subsequent years towards Sandra Bland and Breonna Taylor.

Thirty-five years after her reign of glory and twenty-five years after her passing, the legacy of Flo-Jo was reflected in the dominance of black women in sports in 2023.

(Courtesy: AP Photo/Susan Sterner)

Angel, Simone, Sha’Carri, Coco, and A’Ja all possess the same agency that Flo-Jo had and found ways to incorporate her style into their own. Sha’Carri has her own trademark long fingernails and A’Ja dons the one-legged suit. Angel has the flareful defiance in the face of scrutiny that is endearing. Coco has the exuberance and Simone has the elegance.

They are all disciples of the template set forth before they were born and their continued success is something that would make Flo-Jo incredibly proud.

“She was on the path for what these black women athletes can manifest today” said Dr. Brown. “I think that her legacy is gonna be a long one. It’s already been a long one.”

Excellence begets excellence.

NFL

NFL